American Gods.

It should come as a surprise to exacly no one that when I was in college, I broke in my brand new credit card, my first ever credit card, buying Alice Walker books at Malaprops, a feminist bookstore in Asheville, North Carolina. I walked out, happy with my newly acquired debt, carrying a plastic sack with The Third Life of Grange Copeland, Possessing the Secret of Joy, and Meridian inside it. What is surprising, at least to me, is that these books sat on my shelf, unopened and unread, for almost 15 years.

One day last year I picked up Meridian out of guilt. And I loved it. It was one of the best stories I had read in a long time, and definitely the best I'd read that year.

"Can you believe it took me so long to read this story?" I said to Frog. "I feel really kind of dumb for letting a book this good sit on my shelf unread for so long."

"Well, you know, books are like that," said Frog. "Sometimes you just can't read them until you're ready. And when you're ready for them, they're great."

The same thing happened with Neil Gaiman's American Gods. Steve bought it for me as an anniversary present the year it was published (2001, by William Morrow, imprint of Harper Collins) and I was excited to get it, being a fan of the Sandman and all. I'd been to two (I think) of his readings at Alice Bentley's sorely missed, now defunct science fiction bookstore The Stars Our Destination, and couldn't wait to sit down and read his latest. Four years later it was still sitting there. And just like Frog said, one day last month it seemed to stand out more and more on the bookshelf, asserting itself in front of the others until I had no choice but to pick it up.

I brought it with me on a recent trip doing research on the Lincoln Highway, The United States' first transcontinental highway. I'd made a trip covered approximately half of Route 66 a couple of years ago with Steve, making the journey the destination, and pulling over and examining every roadside attraction along the way. Sometimes the roadside attractions were good, like when we found a very old beekeeper selling jawdroppingly good lavender honey out of the back of her truck, and sometimes jawdroppingly bad, where for the same price as the honey we toured a "petrified tree forest," which turned out to be gigantic piles of crumbled white rocks in a dusty red dirt lot. I love these homages to the open road, these little entrepreneurial testaments to the drawing power of the highway, where anyone can sell anything to anybody driving though. The freedom of the open road is the greatest representation of the spirit of America to me, and the roadside attractions built up beside it are churches honoring that spirit.

American Gods was the perfect book to bring along on a trip like this. The protagonist, 32-year-old ex-con Shadow Moon, whose corny name probably didn't help him in prison any, is paroled early to attend the funeral of his wife, Laura. On the plane ride back home, he is offered a job by a mysterious man named Wednesday. Shadow, whose plans for the future had all been destroyed by Laura's death, agrees to work for Wednesday, in what he believes to be as a sort of personal bodyguard for an old grifter. As it turns out, Wednesday, like most of what's going on in the book, is more that he appears to be. Wednesday, and all of his cronies that Shadow meets, are ancient gods brought to America by the faith of immigrants over the centuries. As more focus and worship is paid to the miracles of modern life - media, superhighways, and the internet - the less power the gods have over human life. As Shadow gets drawn further and further into protecting the gods, he discovers that a large battle is looming over the soul of humanity; a battle between the old gods and the new.

Shadow and Wednesday move from place to place travelling on old, forgotten highways because, Wednesday says, we're not sure whose side the interstates are on. The meeting places of the gods, quite reasonably, are roadside attractions, where human beings are inexplicably drawn to participate in events. When they leave, Gaiman writes, they aren't sure whether they've enjoyed themselves or not.

Gaiman has written a compelling story tackling ominous themes with his trademark gentle darkness, writing about the struggle for the American soul, religious power against scientific power, and which religion? Which science?

Plus, it may be my partisan slip showing, but American Gods seemed to be making subtle commentary on the dishonesty inherent in American politics in general, as well.

American Gods is one of three books in recent memory that have managed to irritate total strangers on first sight, Susanna Clarke's Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell being one because it was too long and should not be read by anyone who was not being forced to, and Gwendolyn Zepeda's To the Last Man I Slept With and All the Other Jerks Just Like Him (title) being the other two.

"Is that a book about Jesus?" asked the man sitting next to me at the counter in a cafe in Ashton, Illinois a block off the Lincoln Highway.

"No. It's about six foot tall bar-brawling drunken leprauchauns," I said.

"Huh," he said, and turned back to his coffee cup. I turned back to the book.

When I reached the point of the Lincoln Highway where Route 66 intersected with it, I got out of the car to look around. If the roads are the spirit of American Freedom, this must be the holiest place around. There were no roadside attractions, just a lone sign marking the historical site. I closed my eyes and tried to let the spirit in. I didn't feel anything at all.

_________________________

American Gods was a Nebula Award finalist and a Hugo Award Winner.

Wednesday, September 28, 2005

Sunday, September 25, 2005

So Say the Little Monkeys.

This playful rhyming book, filled with nonsensical monkey sounds and exclamations of delight, is a fun read-aloud book for small children. Based on a Brazilian folktale, So Say the Little Monkeys tells the story of the tiny black monkeys that live along the banks of the dark-watered Rio Negro, or Black River, in Brazil.

The monkeys live in the tops of the thorn-covered palm trees, where they eat fruit and play all day. Unlike their neighbors the birds, the monkeys do not build a permanent dwelling, and instead spend their nights shivering in the cold, their days shivering in the rain, and sleep on the sharp thorns, even though it is painful. The Brazilian Indians created this amusing tale to explain to their children why the monkeys do not take better care of themselves.

Re-told by Nancy Van Laan, So Say the Little Monkeys is illustrated by artist Yumi Heo, whose illustrations of the monkeys bear a striking resemblance to author Ayun Halliday's drawings of her daughter, Inky.

Van Laan re-tells the legend with a keen ear for sounds that children love to say aloud:

Still they climb, UP-UP!

And they slide, DOWN-DOWN!

They sing, "Jibba jibba jabba,"

swinging round and round.

JUMP, JABBA JABBA,

RUN, JABBA JABBA,

SLIDE, JABBA JABBA,

Tiny, tiny monkeys having fun!

Van Laan cleverly taps into activities that children also enjoy, creating a sense of empathy and cameraderie to the dizzy little monkeys, whose sole purpose in life seems to be devoted to play rather than the depressing, adult details of survival. Unlike the children who are safe and warm in bed, hearing the story read by people who do their worrying for them about food, clothing and shelter, the monkeys have a heavy price to pay for their daytime silliness, encouraging children, one would hope, to place their trust and appreciation in their caretakers.

Which of course, never happens, so just hang that dream up right now.

So Say the Little Monkeys was published in 1998 by Atheneum Books for Young Readers, a Simon and Schuster imprint.

________________________________

Appropriate for ages 2-5.

Sunday, September 11, 2005

Epileptic and Gemma Bovery.

My sister, who is eleven years older than I am, moved out of the house and onto college when I was seven years old. I moped around the house for days, convinced that she'd forget me. She didn't, though, and for the next 10 years always made a point of having my mother drop me off at whichever hippie bachelorette pad she was currently calling home in the Five Points area of Columbia, South Carolina. I loved staying with her, mostly because I missed her, but also because she saw no particular reason to curb her freewheeling hippie bachelorette lifestyle just because her eight year old sister was tagging along. When I was ten I was spending Sunday mornings in bars with my sunglasses-clad sister and the achy, hungover heads of all her friends, grimacing my way through my first screwdriver, or sitting in the back seat of a long white '65 Chevy Malibu, chauffeured around by a man with curly dark hair named Mo, an open bottle of Bud nestled snugly against his crotch. When I shyly gathered my courage to whisper something about drinking and driving, he howled with laughter, brushed his face up against mine in a stubbly kiss and shouted, "No worries, little baby, I put the M-O in "moderation!"

I was twelve when I learned to separate the stems and seeds from the buds, and fifteen when I learned that it was fine to suck back as many Marlboro Reds as you wanted as long as you were in a bar, because it didn't count as smoking if you were drunk.

For reasons my young brain could not fathom, she inexplicably drew the line when she walked into her bedroom and discovered me poring through her collection of Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers and Mr. Natural comic books.

"No!" she said, startling me into wide-eyed confusion as she snatched them away from me.

"But why?" I asked, following her around, hurt.

"They aren't for kids to read; they're for grownups," she snapped. "Now I'm going to pour myself a glass of cabernet. Do you want one? No? No, you probably wouldn't like it. Let's get you some Zinfandel, it's sweeter."

I dropped the subject for the moment, picking it back up again the following morning when she was heavily sleeping off the bottle of red. I slipped into her closet and sat on the hardwood floor for the better part of an hour, blissfully introducing myself to Phinneas, Franklin, Fat Freddy, and of course, their filthy cat. When I went to college myself, I bought the entire collection at H.R. Puff N Stuff, a head shop in Pennsylvania that had somehow managed to avoid a lawsuit from Sid and Marty Krofft. Ever since then, I've always loved alternative comics, even though I've never joined the boys flipping through Marvel or arguing the superiority of Batman over Superman.

I've been especially happy that graphic novels are gaining in acceptance, because it's allowed me to leave my dirty hippie homebase and branch out into reading Spiegelman, Satrapi, DiMassa, the great Bechdel, and of course, the ultimate in graphic novels, Gaiman's Sandman series.

Lately I've been getting into French graphic novelists, and, when that won't do, English graphic novelists who set their stories in France and write the dialogue partially in French. I know, I know, but these are really good.

Gemma Bovery, the faux French one written by British cartoonist Posy Simmonds and published by Pantheon Press (which has an excellent graphic novel section, by the way), was originally printed in weekly serial form in The Guardian. I can't say how it was like to read it in its original form, but Gemma Bovery reads so much like one of them there books without pictures that I feel like it's better to hold the entire story in your hands at once.

Gemma, unsuprisingly, is the modern re-telling of the Flaubert classic Emma Bovery written in comic book form. Simmonds has a lot of story to tell, and as a result, the characters in the illustrations creep around the copious dialogue, typeset instead of hand-lettered. Gemma, a dissatisfied and restless second wife to an emotionally distant husband whose heart is preoccupied mostly with his children from his first marriage. A reluctant stepmother and jealous of the demands made by her husband's first wife, Gemma demands a change of scenery in the northern French provence of Normandy, where she captures the imagination of an intellectual baker, who is the tale's narrator. Helpless in the face of his voyeurism, he watches her self-destructive behavior build to explosive proportions.

The black-and-white, stark illustrations lend well to the tragic tale, and have a decided Edward Gorey influence that lends well to the story that's being told.

The actual French graphic novel, David B.'s Epileptic, is an incredibly ambitious, exhausting, 361 page novel, in classic panel form. The epileptic in question is David's older brother Jean-Christophe, whose severe form of the disease rules not only Jean-Christophe, but his entire family. It is an aching novel, especially if, like me, you are the parent of a disabled child. The entire family revolves around Jean-Christophe's illness. Summers are spent at a macrobiotic camp because his parents met a Japanese guru whose strict dietary regimine seemed to lessen his thrice-daily grand mal seizures. When summer ended, the whole family stayed on, and David and his sister Florence were home-schooled. As Jean-Christophe grows older, with no real cure in sight, his parents grow more desperate and the cures grow wilder. David's father relies on Catholicism, while his mother delves into more secular forms of mysticism, and where the parents go, the children follow. David begins to see his brother's disease as an actual monster, killing the entire family and tearing it apart. The disease begins interferring with not only Jean-Christophe's academic and social life, but David's as well.

David B. captures so well the pain and heartbreak that come with a family's lifelong battle with a severe childhood illness, and the depression of well family members when they realize they must make the choice to either let go, or allow themselves to get sucked down the epileptic whirlpool along with Jean-Christophe.

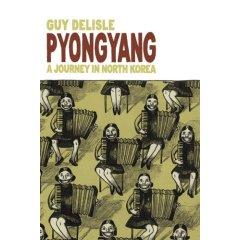

Next on my To Buy list is Guy DeLisle's story of his visit to North Korea, Pyongyang, and I cannot wait. I cannot wait to buy this book. I think about it all the time.

In fact, I think about it so much that last night, when I was sitting at the kitchen table with Alex, coloring with him, I realized that I had absently written "Pyongyang" in blue crayon. Unable to satisfactorily explain why I was writing down the name of the capitol city in the last communist regime to an imaginary House Un-American Activities Committee, I eventually gave up, drew a red flag, signed my work "Commie Mommy" and called it a day.

Tuesday, September 06, 2005

Black Like Me.

Like many Americans, I'm horrified by the damage done by Hurricane Katrina. Like many Americans, I have family missing - my entire family on my mother's side, in fact, who all live in Picayune, Mississippi. And like many Americans, I'm sickened and angered by the callous indifference shown to the victims by our deplorable "President" and his miserable, incompetent, racist administration.

I am angry beyond measure that Barbara Bush, our resident Marie Antoinette, glibly told the press that things were working out very well for the underprivileged, because, after all, they'd lost everything but now they got to live in the Astrodome in Houston. Are things "working out very well" for my family, too, wherever they are? The last we heard from my Aunt Georgia, they had a bathtub full of fresh water to drink. That was a week ago. I can't go and get them - I'm not even sure where they are, but even if I did, the roads are closed except for emergency vehicles, because carjackers are stealing cars for what remains of the gasoline. There is no electricity because there is no gas to run the generators. There are no phone lines, and the cell phone towers have been blown down. Are things working out well for them, Mrs. Bush? How comforting that is for me to hear.

I'm angry beyond measure that in the face of this disaster that New Orleans' poor, mostly black, full-time residents are left to drown, their bodies floating down rivers, being eaten by rats and alligators, while the survivors were systematically dehydrated and starved to death by those who used the city as their own personal place to puke during Mardi Gras in past years. (Unless, of course, you're a teenaged girl willing to whore yourself to the police in order to save your life) Are things working out well for them?*

And I'm angry beyond measure that almost 50 years after John Howard Griffen shaved his head, blackened his face, and walked through Mississippi as a black man, Katrina shows that the attitudes of many white people haven't really changed all that much when it comes to the suffering of the poor and the black.

Black men told me that the only way a white man could hope to understand anything about this reality was to wake up some morning in a black man's skin. I decided to try this in order to test this one thing. In order to make the test, I would alter my pigment and shave my head, but change nothing else about myself. I would keep my clothing, my speech patterns, my credentials, and i would answer every question truthfully.

To say that Black Like Me made an impact on American society - published before the Selma marches, before Rosa Parks, before Medgar Evers, published right at the tail end of Jim Crow - was an understatement. He was burned in effigy in his hometown, the town he lived in his entire life, his family had to leave the country due to death threats, and he himself received death threats until the day he died.

The most common criticism I hear of Griffin is that it isn't right for a white man to get so much attention for saying the exact same things black men had been saying for years. Unfortunately, the simple fact is that in 1957, white people were the ones insisting on defining what is or is not racism. Black people, when they weren't ignored or murdered, were dismissed as complaining, as lazy, as whiners, as troublemakers.

Black people like Kanye West, who stood virtually alone as one man who had access to international media as well as the courage to employ what civil rights activist Dick Gregory referred to as "knee-knocking courage," to speak the truth with a shaking voice. His reward so far has been this, from NBC:

Tonight's telecast was a live television event wrought with emotion," parent company NBC Universal said in a statement issued to the Reporters Who Cover Television after the broadcast.

"Kanye West departed from the scripted comments that were prepared for him, and his opinions in no way represent the views of the networks. It would be most unfortunate if the efforts of the artists who participated tonight and the generosity of millions of Americans who are helping those in need are overshadowed by one person's opinion.

Except it isn't one man's opinion. It's the opinion of millions of black people, who are demanding justice and telling their truths, once again to be accused by whites of "making it racial." 47 years after the publication of Black Like Me and the white people of the United States still feel entitled to declare what is or is not a racial issue.

Do I think George Bush hates black people? I don't know. I know he hates poor people. I know he blames my Aunt Georgia for her poverty, for her inability to leave Mississippi, and can therefore wash his hands of her, and she's white. It would be so easy for me to use her disappearance as proof that the tragedy of New Orleans isn't a racial issue. But I can't pretend that I haven't heard black people being blamed for FEMA's refusal to allow the Red Cross to enter New Orleans, due to the looting and the shooting they all apparently couldn't wait to do (despite the Red Cross' statements contradicting it). I can't pretend I haven't heard that it was black people's fault that FEMA wouldn't drop food packages down to the survivors because the Army was afraid of getting shot. I can't pretend I haven't heard that it was black people's fault for being too lazy to hitchhike out of New Orleans. And of course, we've all heard that black people loot, white people find".

I can worry about my white family and still believe that they were unwittingly caught in two hurricanes; one caused by nature and one by racial indifference. I can believe that Kanye West displayed "knee-knocking courage." And I am so sad to believe that the greatest progress the United States has made is that West will not be murdered for his beliefs - he'll just be accused of being a black man who dares to decide what constitutes racial discrimination.

I suppose he should be grateful, really, that things are working out so well.

_____________________

*from Twisty.<