Cry Yourself to Sleep.

One of the nicest gifts given to readers by artists who take the personal approach with their artistic expression is how neatly it simultaneously presents our differences and similarities. C. Tyler, author of the brilliant Late Bloomer, presents her work from the perspective of one who has traveled farther down the path than some, and allowing us to see the evolution of an individual’s life from innocence to wisdom, and from low times to high. No less valuable is the presentation of life via characters who are just starting off on their path to maturity, especially when presented in such a sweet and melancholy style as Jeremy Tinder’s Cry Yourself to Sleep.

The little graphic novel gives us three loosely overlapping storylines. Jim, a yellow-furred rabbit who loses his fast food job for refusing to wear the fingered gloves that slide off his paws, struggles to make the rent by asking his parents for money. While his rabbit mother is sympathetic, his human father is less so, refusing to accept that he was fired because he is a rabbit (“Don’t play the species card, son.”) and insists that he get a job at his company, where he is trained by an old-timer who resents having to train the boss’ son. Jim’s roommate, Andy, is a video clerk and an aspiring novelist recently crushed by his first rejection letter, and their pal the robot, who wants to discover his humanity and spends the novel literally trying to live as free as a bird.

While the robot story is amusing, it's definitely the least strong of the three stories, and kind of gets in the way of the story of Andy, the sweet-natured video clerk who has reached one of the first of many difficult adult choices adults must face: should he continue to work toward life as a writer, or should he opt for the stability of a steady paycheck, putting his dreams aside in hopes that he will be another Late Bloomer?

Additionally, Andy's shy, gentle courtship of a video store customer is so enearing that Cry Yourself to Sleep should be required reading for all 20-something girls who are interested in finding out what really lurks in the hearts of their male counterparts - it even fits neatly into a purse.

Although Tinder's debut novel is so small it could be easily overlooked when surrounded by larger, more sprawling and ambitious works, it's well worth looking out for. As Cry Yourself to Sleep proves, it's often the soft, gentle voices most worth listening to.

_______________________

Cry Yourself to Sleep

by Jeremy Tinder

2006, Top Shelf Productions

Softcover

81 pp

ISBN: 1-891830-81-3

This review originally appeared at TARGET="_blank">J LHLS.

Monday, May 29, 2006

Saturday, May 27, 2006

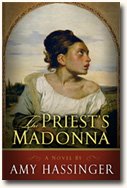

The Priest's Madonna I was sitting in one of the training rooms at my new job at the Big Machine, learning how to use the corporation's computer system and chatting with another trainee. Amy Hassinger's new novel The Priest's Madonna was propped next to the monitor, waiting until my lunch break for its turn for my attention.

I was sitting in one of the training rooms at my new job at the Big Machine, learning how to use the corporation's computer system and chatting with another trainee. Amy Hassinger's new novel The Priest's Madonna was propped next to the monitor, waiting until my lunch break for its turn for my attention.

"I don't think I'd like that book," said the other trainee. "It looks too intellectual for me. And the cover is too creepy."

She pulled a paperback out of her overstuffed purse. "This is more my speed," she said. "Ack," I may have said in response.

"Ack," I may have said in response.

The old cliché warns us not to judge a book by its cover, but we all know this isn't necessarily true. As you can see, covers are not only designed to lure in the reader, but are also designed to warn them away.

The Harlequin romance cover featured here tells the reader, "This book is so awful you could have written it yourself!" For some unfathomable reason, this appeals to some people. Amy King's excellent cover design of The Priest's Madonna successfully weeds out readers that hate to read, and lures in others who sense by looking at the darkly romantic cover that they're in for a gothic historical romance filled with mystery and tragedy. And their assumptions would be pretty much on the money.

King found this gorgeous oil painting via Erich Lessing's Culture and Fine Arts Archives, a resource of more than 37,000 digital photographs of artwork. This painting is such a perfect fit for the book that it's difficult to believe it wasn't created just for it. Entitled "Jeune orpheline au cimetiere," ("Young Orphan in the Cemetery" or "Young Orphan Girl in a Cemetery," depending on your translation), the painting was created in 1824 by Eugène Delacroix, the most important of the 19th century French Romantic painters. Its gorgeous brushstrokes and the intense, upward stare of the beautiful, romantic young girl implies possible danger and a strong sense of mysterious desperation.

The vague sense of danger and desperation is mingled with beauty and romantic longing is at the heart of the novel and radiates throughout.

So, aspiring writers, if you're keeping score at home:

If you want people to read your book, hire

Olga Grlic, whose design of What Do You Do All Day? I've already gushed about, but here it is again:

and now, Amy King.

Olga Grlic

Amy King

That is the official Books Are Pretty shortlist for cover designers.

Now, onto the book itself. Happily, The Priest's Madonna lives up to all the promise the cover delivers.

Based on an actual French mystery, The Priest's Madonna offers Hassinger's theory on Bérenger Saunière, the 19th century country priest of the church in the village of Rennes-le-Château. After living a simple life for many years, Saunière abruptly comes into a vast amount of unaccounted-for wealth, which he lavishes on church reconstruction and on his mistress, Marie Dénaraud, who the village referred to as "The Priest's Madonna," because he worshipped her as he should have worshipped Marie Madeleine (Mary Magdalene).

Several theories abound as to how he acquired his vast amount of wealth, and Hassinger carefully reconstructs the events prior to the mystery and bases her theory on several pieces of historical facts surrounding Rennes-le-Château, combining twelfth-century Visigothic princesses, secret tombs and tunnels, mysterious and ominous letters bricked into the walls of the church.

Running parallel to the romance between Dénaraud and Saunière is the story of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, and Hassinger draws riveting parallels between the two stories and, in the end, connects them both together in a way that both illuminates and obscures the connection between the lives of the secular and the holy.

The Priest's Madonna, though certainly no Harlequin Romance novel, is nonetheless a riveting and thoroughly enjoyable novel, combining fact and fiction to create a historical romance of the very best kind.

____________________

The Priest's Madonna

by Amy Hassinger

2006, G.P. Putnam's Sons

Hardcover

310 pages

ISBN: 0-399-15317-9

Tuesday, May 23, 2006

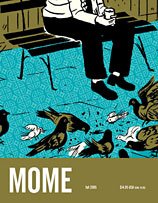

Mome.

The Fall 2005 issue of Mome, from Fantagraphics, is an anthology of comics from several contributors. Printed on high quality paper with a fancy glossy sheen, Mome comes across like a Virginia Quarterly Review or Ploughshares – its serious presentation demands that the comic medium be considered with the same respect as any literary art form. On many levels, Mome succeeds admirably. It features a wide variety of artists with just as many separate styles and influences. Some take a traditional approach, like Jonathan Bennett’s “Needles and Pins,” and some dip into the experimental, like the minimalist “Event,” Anders Nilsen’s emotional tale told almost entirely by using different colored squares. While some of the comics in the anthology fall short of the high standards one would expect from a top literary journal, there are far more that are well-deserving of serious literary appreciation.

Sophie Crumb, who by now must be utterly sick of the inevitable comparisons to her famous father and, by extension, to underground commix in general, is about to get it again from me, so close your eyes: "Parker, the Vegan Bike Punk," looks like an R. Crumb drawn, G-rated version of Gilbert Sheldon’s "Little Orphan Amphetamine," and the message is the same - it's darned hard to hide that middle class bourgeois core. For example, I'll admit how easily Crumb the Younger exposed my own bourgeois core – I prefer her gently humorous "Parker" over the violent and depressing "Amphetamine." Crumb’s story makes the exact same point, but without the sledgehammer.

Jeffrey Brown’s "Our Jam Band Is Going to Be Sweet" is a tale as well-told as any story in The New Yorker. What seems at first to be a straightforward detective story along the "Law & Order" lines. Once the story begins to draw to its close, you realize that it wasn't about policework at all, but rather a revelation of apathy and betrayal. The spine of the piece is the pathos of the human condition, and the detective story line is only what cloaks it.

Andrice Arp’s "Cormorant Feathers" is a visual adaptation of a Japanese creation myth, explaining the origin of Japan's ruling class and their descent from gods. The blue/black two-tone coloring is reminiscent of the Ignatz series, as is the moody, dreamy quality of the illustrated narrative as a whole. "Feathers" recreates the birth of the father of Jimmu, Japan's legendary first emperor, and by dusting off classical mythology and repackaging it for comic book readers, comes across in this series as one of the two most creative stories presented.

Although Mome clearly wants to prove that comics are a serious artform, this isn’t to say the creators take themselves too seriously. In an interview with Publisher’s Weekly, editor Eric Reynolds says, "There's something fitting in having an anthology of contemporary talent named after an archaic word meaning 'blockhead.'"

____________________

Fantagraphics 2

Gary Groth & Eric Reynolds, Eds.

Fantagraphics, 2005

Softcover

136 pp.

This review originally appeared at TARGET="_blank">J LHLS.

Monday, May 22, 2006

The Bowl Is Already Broken

Mary Kay Zuravleff’s The Bowl Is Already Broken is what the more intellectual among us will be taking to the shore for beach reading in lieu of Lauren Weisberger’s The Devil Wears Prada. Like Weisberger’s bestseller, The Bowl Is Already Broken covers a topic the author knows inside and out – her job. Prada is filled with juicy gossip about the inside and infighting of the fashion world at one of its top magazines, while Bowl revolves around juicy gossip about the inside and infighting at one of the world’s top museums. Both are packed with enough information to let the reader know they really have a firm grasp on their subject matter, but that’s where the similarities end.

The Bowl Is Already Broken begins in disaster. Promise Whittaker, the petite acting director of Washington D.C.’s Museum of Asian Art, (a thinly veiled Arthur M. Sackler Gallery), is heading up a ceremony with various invited dignitaries to receive a million dollar porcelain bowl. It is her first event as acting director, and the worst possible thing that could happen, happens. Part one of the book revolves around the six months preceding the calamity, and Zuravleff painstakingly and seamlessly weaves each individual thread of the novel’s scheming characters together before presenting, at the end of part one, that there’s much more to the initial disaster than meets the eye.

Early in the novel, Museum director R. Joseph Lattimore receives a carelessly worded memo that describes, almost as an afterthought, the plans to dismantle his museum and replace it with a food court. Naming Promise as his heir, Lattimore quits, and he and his wife Emmy take off to the Taklamakan Desert, a land rife with civil unrest, to participate in an archeological dig. The book then flashes back and forth between Promise and Joseph, contrasting and comparing the struggles they face. Promise, who up until now has had her nose buried firmly in ancient texts of Rumi, the 13th century Persian poet, now must bury her nose in one personal disaster after another: the unsympathetic Asian Art curator Min Chen, who embezzled museum funds to pay for her uninsured fertility treatments, Chinese porcelain curator Arthur, his bitterness that he was not made curator battling with his fondness for Promise, sleeps with narcissistic coworker Talbot in order to acquire Talbot’s exhibition money for his own use, and her own out of control personal life, complete with an unplanned pregnancy. Oh, yes, and her increasingly desperate measures to save the museum from turning into a fast food Chinese restaurant called Wok On.

As the infighting grows, one begins to look forward to the parts of the novel that are focused on Joseph, and his peaceful, simple kidnapping at the hands of religious fundamentalists and the subsequent bludgeoning that follows.

The white stem bowl looked especially pure. Slightly deeper and stockier than a champagne glass, it had a thin flared lip and thin parallel grooves cut into the stem. But wait! There’s more! Promise leaned close enough to fog the case with her breath. The bowl was lighly carved with elaborate motifs of its own: floral sprays and lotus blossoms as well as the Eight Auspicious Symbols of Buddhism…Look and then look again: this was exactly what an exhibition was supposed to inspire.

Zuravleff manages to do pretty much the same in her novel, too. Unlike such novels as The DaVinci Code, where the overly dramatic twists and turns are broadcast larger than life and each chapter ends in a cliffhanger, Bowl builds its intrigue quietly letting the reader ferret out each character’s plots and intrigues as they make their plans for their own personal power.

It reads as cool and dry as a museum, almost a bit too cool. The book did not click into place until I mentally cast Holly Hunter as Promise and Rupert Everett as her coworker, curator Arthur. Then it caught on for me, and I enjoyed the multiple story lines Zuravleff spun out, as well as the education on Asian art history that she seemed eager to impart to her readers. Although I can see how the endless stories about the Persian poet Rumi or the evolution of the glazing process used by ancient Chinese craftsmen could become tiresome, nerds such as myself may appreciate an education from someone as knowledgeable as the author. (My favorite historical bit was the story of Mir Ali, the distinguished 14th century calligraphist who was abducted from his home and his family to be a court scribe in Bukhara. He wrote his laments onto pieces of paper, which somehow survived to the present day: "I have no way out of this town/ this misfortune has fallen on my head for the beauty of my writing./ Alas! Mastery in calligraphy has become a chain on the feet of this demented one.")

With the exception of one extraordinarily ham-handed metaphor – on the day that Promise finds out that is she is both the new Acting Director and pregnant, Promise winds up the day by literally juggling – Zuravleff maintains her cool, detached touch throughout. (Much better was the part bookmarked for me by the publisher’s publicist with a note that read “Any mom could relate to this scene.” A scene of hungry children and a feces-smeared dog coupled with the exhaustion of early pregnancy? Yep, the publicist was right. Been there.)

If this light touch is what you’re looking for in a novel, The Bowl Is Already Broken is the book for you. Just skip over that juggling scene on pages 156 and 157 and you’ll be just fine.

____________________________

The Bowl Is Already Broken

By Mary Kay Zuravleff

Picador Press, 2006

Softcover

451 pages

ISBN 0-312-42498-1

Thursday, May 11, 2006

The Long Secret.

The town of Water Mill, New York keeps popping up at work, and no surprise, really, that a lot of people who do big money business with Big Machine call Water Mill home. In the summer, anyway, when the kings of Manhattan pack up the family and ship them off to the sixth richest zip code in the country.

I hadn't thought about Water Mill in decades, so long that I didn't remember ever thinking about it at all. I looked it up on Mapquest, but seeing the tiny dot indicated on the island off New York didn't ring any bells. Then it came to me: Harriet M. Welsch. Harriet's parents, and the grandmother of Harriet's excruciatingly shy friend Beth Ellen Hansen, had summer homes in Water Mill, and the town itself and its inhabitants were featured in the second of Louise Fitzhugh's Harriet books, The Long Secret.

Last week the young, frazzled assistant of a Water Mill summer resident called us repeatedly on behalf of her boss anxiously checking and double-checking to make sure that we were adequately meeeting her boss' needs.

"It's just that it has to be exactly right," she pleaded. "He likes to have everything just right!"

Unlike the rest of us, I assume, who don't really care whether we get what we pay for or not.

As Beth Ellen ran across the room to where the ornate bellpull was concealed behind the heavy drapes she heard [her mother] Zeeney say, "And that's the first thing that must go. I can't imagine what possessed her father to name her Beth Ellen."

"I believe it was his mother's name, wasn't it?" said Mrs. Hansen, rolling her chair closer to the couch.

..."That doesn't matter a whit now," said Zeeney. "It must be changed. It's perfectly terrible."

"You can't just change someone's name when they're twelve years old," said Mrs. Hansen in her close-to-anger voice.

..."We can, at least, call her Beth!" said Zeeney with what seemed like rage.

It wasn't until now that I fully appreciate the genius of Fitzhugh. In all three books featuring young Harriet and her friends, Fitzhugh wove in a very adult, very pointed social satire of the idle New York rich in the mid 1960's, knowing full well her most cutting dialogue and blistering character sketches would fly over the heads of most of her little readers.

In The Long Secret, Harriet spies on Beth Ellen's sociopathic mother and all her friends and, even though she sees and reports on all, she doesn't always realize what she's seeing. Her analyses of the situations are flat with incomprehension.

When re-read as an adult, the antics of the adults suddenly click into place, and all the rivalries and insults are made clear, sailing over the heads of the children and, if the opportunity arises, the children are used to insult their parents.

Welsch...are you Rodger Welsch's daughter?" Zeeney leaned forward.

"HARRIET!" said Mrs. Welsch in that certain brisk tone which Harriet knew could not be disobeyed. This time, however, she was too enthralled to do anything but stare at Zeeney.

"Yes!" she said proudly.

"...Well," she said doubtfully, "you don't look a thing like him. Are you sure?"

Although The Long Secret is a "Harriet" book, the protagonist is actually the timid Beth Ellen, poor little rich girl. Rejected and abandoned by her cold but beautiful mother, Beth Ellen is raised by her grandmother until the summer Beth Ellen turns twelve. It is then that her mother, now a stranger, whisks back to New York from Europe to mold her daughter in her image. It is a sad little book in many ways, really. Beth Ellen spends much of it grieving the loss of her childhood and fighing its demise in her passive way by slipping away with Harriet and their friend Janie, (aka PZ Myers' long lost daughter*) to discover the secret identity of the person who has been terrorizing Water Mill residents by leaving nasty, Biblically-related notes around town, pointedly smiting the vain right on their particular Achilles' heel.

As the summer draws to a close and preparations are made to take Beth Ellen from her friends and the grandmother who loves her, the passive little girl must decide whether or not she will, for the first time in her life, fight.

The straightforward plot is entertaining enough for girls to enjoy, but it is the details of the adult lives, not dumbed down or held back, that fully flesh out the book and give the book its intense richness. Who doesn't remember sitting in on adult conversation and feeling tension in the air, but not understanding its genesis?

"And this - Zeeney was across the room in one white swoop - this must be your mother!" She extended a hand to Mrs. Welsch. "I'm delighted to meet you. I've always wanted to see who Rodger married."

"Oh?" said Mrs. Welsch and for some reason looked at Harriet as though she wanted to tear her limb from limb.

"I'm so sorry!" said Zeeney with a great show of white teeth, "I'm Zeeney Baines. I was Zeeney Hansen. Rodger and I used to play tennis together. We haven't seen each other since we were fifteen years old. He's never mentioned me?"

Mrs. Welsch looked calm. "I know your daughter quite well," she said pleasantly, "and of course, your mother."

"Mmmmmmm," said Zeeney, "naughty Rodger. Not even mentioning me...What DAYS those were...what CHILDREN we were...Oh, the pity of it all...Les histoires d'enfance..."

Harriet's eyes were bugging. She watched her mother's eyes narrow.

Zeeney seemed to pull herself together. "You weren't around then were you, dear? I don't seem to be able to place you...You weren't there, around the Club, I mean?"

"Oh yes," said Mrs. Welsch sweetly, "but I was much younger, of course."

"Of course," Zeeney hissed between her teeth and left the table.

...Mrs Welsch looked around the room. "Why don't you go ask Beth Ellen if she wants to sit with us in here. They don't seem to be paying much attention to her."

Fitzhugh could have left all the adult schemes and in-fighting out of her books, but she didn't. She pulled no punches, and wrote the truth as she knew it. It is this type of complexity and sense of reality, where children are on the verge of understanding, that creates a memory that lasts a lifetime, a memory that can be triggered years later, when just the mention of a small town in a completely different context brings back a flood of images of people and places seen only in the imagination of a child.

________________________

*Here's Janie explaining menstruation to Beth Ellen and Harriet. Tell me this child didn't grow up to wage war against Creationists:

"It happens to everybody, though, every woman in the world, even Madame Curie. It's very normal. And I guess, since it means you're grown up and can have babies, that it's a good thing. I, for one, just don't happen to want babies. I also have a sneaking suspicion that there're too many babies in the world already. So I"m working on this cure for people that don't want babies, so they won't have to do this."

Beth Ellen looked up at Janie and asked tentatively, "do those rocks hurt you too?"

"Rocks?" Janie yelled.

"Those rocks inside that come down," said Beth Ellen timidly.

"WHAT?" screamed Harriet. "Oh, well, if they think I'm gonna do anything like that, they're crazy."

"There aren't any rocks. Who told you that?" Janie was so mad she stood up. "Who told you there were rocks? There aren't any rocks. I'll kill 'em. Who told you that about any rocks?"

Beth Ellen looked scared. "My grandmother," she said faintly. "Isn't that right? Aren't there little rocks that come down and make you bleed and hurt you?"

"Right? It couldn't be more wrong." Janie stood over her. "there aren't any rocks. You got that? There aren't any rocks at all!

"WOW!" said Harriet. "ROCKS!"

"Now, wait a minute," said Janie, holding up her hand like a lecturer, "let's get something straight before you two get terrified."

"They both looked up at her. Beth Ellen was frightened and confused. Harriet was angry and confused.

"Now, you must understand," said Janie, looking very earnest, "that the generation that Beth Ellen's grandmother came from is very Victorian. They never talked about things like this, and her grandmother thought that telling her this was better than telling her the truth."

"What's the truth?" asked Harriet avidly.

Beth Ellen didn't care about the truth. The rocks were bad enough to think about. What could the truth be?

"That just goes to show you," said Janie, looking like a stuffy teacher, "that people should learn to live with fact! It's never as bad as the fantasies they make up."

"Oh, Janie, get on with it," said Harriet. "What is the truth?"

"Ah, what a question," said Janie.

"JANIE!" said Harriet in disgust.

"Okay, okay," said Janie as though they were too dumb to appreciate her, "it's very simple. I'll explain it." She sat down as though it would take a long time.

"Now, you know the baby grows inside a woman, in her womb, in the uterus?"

They nodded.

"Well. What do you think it lives on when it's growing?"

They both looked blank.

"The lining, dopes!" she yelled at them.

They blinked.

"So, it's very simple. If you have a baby started in there, the baby lives on the lining; but if you don't have a baby, like we don't, then the body very sensibly disposes of the lining that it's made for the baby. It just comes right out."

"It falls right out of you?" screamed Harriet.

Oh, thought Beth Ellen, why me?

"No, no, no. You always exaggerate, Harriet. You would make a terrible scientist. You must be precise."

____________________

The Long Secret

by Louise Fitzhugh

Dell Publishing Company, Inc

copyright 1965

paperback

275 pp.

ISBN: 0-440-44977-4

Saturday, May 06, 2006

Late Bloomer.

As the second-wavers like to say, the personal is political. This short little soundbite, so pithy and perfect and catchy, with the dainty plosives enveloping the two letter verb like puffy lips, top and bottom, like a kiss. And like any effective slogan, its ceiling can become so high and broad that one loses sight of the fact that, down on the ground, making the personal (private) into the political (public) can kind of suck sometimes.

Writers who have the compulsion to pour their hearts and lives out on the page make the choice of what to hold and what to show, and often even hide things right in the middle of what they show (unlike fiction writers, who show things right in the middle of what they hide. Or something.) So it's understandable that readers confuse the writer with what she's written, because what she writes is true, or, as David Sedaris says, true enough.

R. Crumb, a cartoonist who has drawn panel after panel of his very specific sexual fantasies about very specifically drawn women, still drew a very revealing image of himself during the filming of the documentary about his life Crumb. In the drawing, he's crouched in the position that all Cold War children remember well - knees drawn up to the chin, arms cradling the head, eyes closed tight in preparation for the nuclear flash. Surrounding him on all sides are dozens of cameras.

Thinking back to a cartoon he drew of himself riding piggyback on a big-legged woman with no head, I thought, "What could he possibly have left to keep private?"

And when I read his introduction of C. Tyler's autobiographical cartoon compilation Late Bloomer, I was startled when he wrote, "the level of honesty about herself is...shocking at times."

She shocked R. Crumb? If you've seen an R. Crumb comic where he lays his racism and misogyny right out there, you, too, would want to know exactly what's inside Carol Tyler that she's willing to show. And is it true? Is it true enough? Exactly what kind of person is this C. Tyler, anyway? Is she making the personal political, or is she just telling stories, or what? Imagine my surprise when, after I read Late Bloomer, I discovered that what shocked R. Crumb was nothing more than the inside of my own heart.

Which, I think, is the key of the personal narrative's appeal. Carol Tyler's work exemplifies the ability of the artist to lay it bare and confess all, drawing together the common threads of humanity with a unique flair that makes you wonder what will happen next.

In two of her strongest pieces, "Uncovered Property" and "The Outrage," Tyler masterfully combines both commonality and individuality, the first with a hilarious and sweet childhood anecdote, and the second, the tale I suspect shocked R. Crumb, covers the all-too-familiar horrowshow landscape of any woman who has suffered from post-partum depression.

Other stories include similar themes of dark domesticity; pointed critiques of church elders portrayed as profane on Saturday night as they are pious on Sunday, elderly women manipulated by con artists promising true love, and an achingly true-to-life horror story of being trapped at an airport with a toddler and a headcold. The story that was my sentimental favorite, however, is "Once, We Ran." There isn't much to it, really, just one page describing a small perfect bubble of a moment when she and her little daughter, in matching red skirts, dance on the blacktop of their driveway before going inside the house, because, as she says, details like these tend to disappear.

One can't help but vow to scrapbook or journal the perfect details of your life with your child just a bit harder after reading that important yet simple wisdom, even though the majority of us won't bloom into the artist that Tyler has after the last of our chicks leave the nest.

Although it's obvious Tyler has the chops, her style does take some getting used to. The dialogue in Late Bloomer overlaps and fills the panels, and song lyrics from a radio drawn into several scenes simultaneously weaves through. Once the reader adjusts, however, she becomes totally immersed in Tyler's flower-filled , animated life.

Tyler dedicates her book to "anyone who has deferred a dream due to raising children or caregiving," to late bloomers everywhere. Tyler, like so many women before her, deferred her own dream to spend years in the service of others. It is inspiring indeed, to find that after twenty years of living her creative life in the margins, Carol Tyler has burst out into a full bloom of brilliance, creating something truly inspiring - a mommy book without saccharine or excessive complaint, a testament to talent and creativity shining through at last, no matter what.

_______________________

Late Bloomer

by C. Tyler

Fantagraphics Books, August, 2005

Hardcover

134 pages

ISBN: 1-56097-664-0

This review originally appeared at TARGET="_blank">J LHLS.