Dinner and a Show.

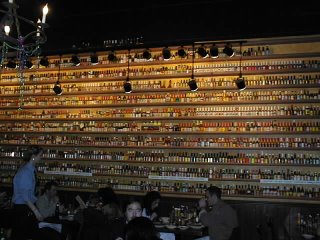

Last week I called Steve after a long day toiling away in the salt mines at Big Machine and asked him if he and the kids wanted to meet me at Heaven on Seven to use the last gift certificate we had. Originally we'd gotten our hands on four of them, and now we were going to meet for one last meal of crabcakes and gumbo before our free ride ended.

This time, as every time, each of us set personal goals for our visits. Alex's and Christopher's goals were very similar: Visit One: I will touch each bottle of hot sauce on the wall.

Visit One: I will touch each bottle of hot sauce on the wall.

Visit Two: I will collect all the strings of beads strewn across the lighting fixtures.

Visit Three: I will take off my sneakers and lie on the floor in front of passing waitstaff. (That was mostly Christopher.)

Each of their personal goals conflicted directly with the personal goal of Steve and me, which was:

Visits One to Three: Get the children to sit down, shut up, and eat.

At last, at Visit Four, our goals totally matched. They adjusted. They are now ready to enjoy nice, peaceful meals at Heaven on Seven. And so now of course we're out of gift certificates and won't be able to go as often.

Halfway through the meal, a woman with a scarf draped around her neck like a big green fringey bib was seated next to our better-behaved-but-still-lively table. She placed her order, then opened a book.

At about this time, Alex and Chris asked if they could walk over to an empty section of the restaurant and look at a painting. I said yes because 1. They asked, rather than just darting over there, and 2. the section was free of patrons to annoy.

It was still a mistake, because once they got up and walked around, it reminded them of how great it is to get up and walk around, and I had to start threatening them with a loss of ice cream to get them to sit back down.

As we all know, once the threats begin, it's over. We called for the check and I kept an eye on the woman with the green scarf, who kindly ignored the festivities at our table and kept her eyes on her book, even when Christopher dropped a dollop of ice cream off his spoon and onto the floor.

"We have to go to the bookstore after Heaven on Seven!" Alex informed us. "We have to go to the bookstore after Heaven on Seven, because that is what we do."

He was right. That is what we do, so when the check arrived we banged out of the restaurant and aimed ourselves toward Anderson's Bookshop. A banner hanging from the awning read, "Author Signing Tonight 7:00 pm."

"Ooh, author signing," said Steve.

"I think they just leave it hanging there all the time," I said, "every time we come here that sign is up."

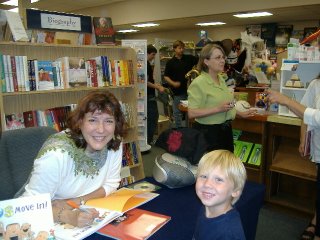

I still think that's true, but maybe the sign and an actual author signing coincided, because author Caroline Crimi was there to read two of her books, The Louds Move In, and Henry and the Buccaneer Bunnies. I asked Christopher if he wanted to listen to a story and he was all, "whatever," so we sat down with a handful of other children on the metal folding chairs the owner had set out.

Crimi, obviously disappointed by the small turnout, brightened a little bit when she saw Christopher.

"Hey, I know you!" she said. "You sat next to me at the restaurant!"

Christopher gave her a look like, "There were other people at the restaurant?" but I remembered her: it was the lady with the green scarf and the bad luck to have been seated right next to us.

A few minutes later, Alex wandered over to the chairs wearing an oversized Mad Hatter's top hat and a pair of catseye reading glasses. He sat down next to me and Crimi read the first book, The Louds Move In. "I was coming out of Blockbuster," she said, "when I heard what I thought was a group of about thirty second-graders screaming behind me. It was unbelievably loud, and when I turned around, I saw it was a family of four. 'I'm glad they don't live next door to me,' I thought, and then the idea popped into my head and I went home and wrote this book."

"I was coming out of Blockbuster," she said, "when I heard what I thought was a group of about thirty second-graders screaming behind me. It was unbelievably loud, and when I turned around, I saw it was a family of four. 'I'm glad they don't live next door to me,' I thought, and then the idea popped into my head and I went home and wrote this book."

She had the kids, about six in all, come up front with her and make the sound of the Loud baby crying whenever it appeared in the text. Christopher loved this bit of audience participation, too, and after a certain amount of bashfulness from the young man in a giant hat and funky glasses, so did Alex.

The Louds Move In took that family Crimi saw at Blockbuster and had them move into the world's quietest neighborhood, where their new neighbors never spoke to each other and engaged in quiet hobbies like dusting china and collecting pincushions. At first their neighbors are horrified by their screaming new neighbors, but soon learn to appreciate the variety their new neighbors bring to their lives.

The kids got pretty whipped up, thanks to their active participation and Crimi's enthusiastic reading. After the story, she had the kids throw pincushions into a bucket for sticker prizes before starting in on Henry and the Buccaneer Bunnies. Crimi's tale of the bloodthirsty, swashbuckling bunnies led by nebbish little bookworm Henry cracked Christopher up. The idea of bunny rabbits pillaging, mauling, and terrorizing was too much for him, and he laughed that loud, infectious baby laugh that's impossible not to enjoy hearing, especially if that baby is laughing at something you wrote.

When the books had been read and the book signing began, Crimi signed copies of each book, one for Alex and one for Christopher. "When I saw you at dinner, I thought you might be coming to the reading," she said. "I hoped you were."

"When I saw you at dinner, I thought you might be coming to the reading," she said. "I hoped you were."

"I hope we didn't ruin your dinner."

"Oh, no," she said, "but every time I go to dinner I always get seated next to kids. I don't know why that is, but it never fails to happen."

I didn't have the heart to tell her it was a gift certificate that brought us together rather than set plans to attend the reading, but the kids had such a great time, and Crimi made it so much fun that I ended up wondering why exactly it is that we don't go to book readings more often. Maybe next time we'll make plans to be there without being lured in by the promise of Cajun food.

_________________________

The Louds Move In

by Caroline Crimi

2006 by Marshall Cavendish Children's Books

Hardcover, 32 pp

ISBN: 0761452214

Henry and the Buccaneer Bunnies

by Caroline Crimi

2005 by Candlewick Press

Hardcover, 40 pp

ISBN: 0763624497

Monday, June 26, 2006

Friday, June 23, 2006

House of Leaves.

What lurks inside a great horror novel? The revisiting of our childhood fears? Being forced to examine our phobias right up close? The thought of your children in peril? Having to slog through hundreds of pages of academic wankery? If these are the criteria for a horror novel, then House of Leaves is one of the greatest of all time.

I didn’t actually mean to sound so flip about it – really, I didn’t. It’s just that there’s so much layering in Mark Danielewski’s debut novel that if I peeled all those layers away, it would take almost as long to review it as it took him to write it.

House of Leaves, published in 2000, had been floating around the internet for quite awhile prior, giving it a certain cult status even before it was published, and it still has a strong internet presence, in particular at the official House of Leaves website, where the novel’s myriad riddles are passionately discussed.

At its core is the story of Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist Will Navidson and his partner, model Karen Green, who buy a house in Virginia. Navidson, or “Navy,” has agreed to cut back on his work-related travels in order to spend more time with his family. Unable to stop working completely, he sets cameras up all over the house, to turn his settling into family life with Karen and their children, Chad and Daisy, into yet another project.

All is going according to plan until one day, when the family returns from a trip to Seattle to discover a mysterious door that has suddenly appeared in the middle of a previously empty wall. Even curiouser, when Navy opens the door, he discovers that instead of leading to the room behind it, as it should, it opens instead to a long black hallway. Further investigations reveal the startling discovery that the house is larger on the inside than it is on the outside. As Navy’s obsession with the house grows, so does the inky blackness, turning the hallway into a freezing cold, pitch black maze that stretches on for thousands of miles. Eventually, he and a team of explorers disappear into the mysterious blackness, where they are forced to confront their deepest fears.

Except that’s not what the book is about at all.

Navidson’s camera work is released as a documentary called The Navidson Record, which is endlessly opined upon by just about everybody from Hunter S. Thompson to Rosie O’Donnell, and countless academics. Hundreds of pages are devoted to meta-discussions about the plot and What It All Means.

Except it’s not about that, either.

The Navidson Record, it turns out, is actually the fictitious work of an old blind man named Zampano, who scrawled his epic on scraps of paper stuffed in a black trunk in his apartment. The trunk is discovered when Zampano dies a mysterious death, and his life’s work is reconstructed by a tattoo artist’s apprentice named Johnny Truant, who spins out a narrative of his own in the footnotes, chronicling his own growing obsessions with the Navidson house, and his eventually decline into serious mental illness.

Except that may not be true, either, as hinted by coded messages within the text, contradictory information, startling clues, and mysterious illustrations. As overwhelming as this book is, it is often frustrating. The post-modern meta-discussions from fictional academics and the heavily footnoted fictional sources can get a bit tedious in parts, squashing the eerie separate story lines of both Truant and the Navidson family. And then there’s that layout, designed by Danielewski to force the reader to maintain the same pace as the characters in the book. When the characters are running, there is only one word on each page for 25 pages. If they’re in a cramped part of the house the words are bunched up all in one of the corners. If the characters are disoriented, the words are scattered across the page and have to be scooped up and put back in order.

And then there’s that layout, designed by Danielewski to force the reader to maintain the same pace as the characters in the book. When the characters are running, there is only one word on each page for 25 pages. If they’re in a cramped part of the house the words are bunched up all in one of the corners. If the characters are disoriented, the words are scattered across the page and have to be scooped up and put back in order.

With the possible exception of David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest, I can't think of a more challenging or original work, and it's unimaginable to think that a single reading could unlock all the mysteries in House of Leaves.

If you’re ever stranded on a desert island, and you need one book that is different every time you read it, you couldn’t find a better book to have with you.

_______________________

House of Leaves

by Mark Danielewski

2000 by Pantheon Books

Paperback

709 pp

ISBN: 3-375-42052-5

Thursday, June 22, 2006

The List: A Love Story in 781 Chapters.

1. You start reading The List on your lunch break.

2. You wonder if the author keeps the same second person narrative throughout the whole book.

a. Yep.

3. You wonder the same thing about the list-like format.

a. Also, yep.

4. Your girlfriend tells you it looks like something you’d read on the toilet.

5. You agree wholeheartedly and decide it’s a novelty book.

6. You worry about hurting the writer’s feelings if you don’t like it.

7. You wonder how to review it.

a. You think about not reviewing it at all.

b. You brood.

c. And brood.

d. And brood.

e. Eureka!

8. You get paranoid that someone has already reviewed the book using a list-like format.

9. You consult Google and find nothing similar.

10. It’s on.

11. You wonder how many gender clichés appear in the book.

a. Single girls love to shop!

b. They own cats!

c. They take forever in the bathroom!

d. They think they’re fat!

e. They obsess about men!

12. You stop when you realize the answer is probably 781.

13. You don’t finish reading the book.

14. Instead, you give the book to a younger, single coworker.

15. She loves it so much she begins reading it right away, both to herself and out loud to anyone who will listen.

16. She gets very excited about it.

17. What do you know, anyway?

______________________________

The List: A Love Story in 781 Chapters

by Aneva Stout

Workman Publishing Company

April, 2006

Hardcover

96 pp.

ISBN: 0761142169

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Para Para Max: The Moves 101.

I have to confess I know virtually nothing at all about anime. My kids were too little for the Pokemon mania, so the most exposure I have to it is watching Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away. This is a little like saying I’m qualified to review movies because I watched Citizen Kane once.

This means I had to do a little research, and I do mean little, about the subject so could at least get a working definition of what is a huge, already much-discussed topic. When poking around on the internet, I learned that anime dancing is a huge industry in Japan, and most of the A list musicians record music for Japanese cartoons, which in turn becomes a big part of Japanese pop music. It doesn’t really seem too dissimilar from, say, Radio Disney, which plays Nathan Lane singing “Hakuna Matata.” It’s just that there’s a lot more focus on that sort of thing in Japan, it seems.

Because of that, it isn’t a surprise that special club dances were created for anime music, and that’s where Para Para Max comes in.

The Para Para dance craze swept Japan around 1999-2000, which means I’m at least six years behind in my Japanese pop culture knowledge. This is fine, because you would expect a fat Midwestern housewife to be exactly six years behind any popular trend, so reviewing an instructional DVD for a dance craze that was peaking more than half a decade ago sounds just about right.

In Para Para dancing, there are specific, preset movements for each song that everyone does at the same time. Wikipedia makes the comparison to line dancing, which is true, but it’s slightly more complicated. It’s sort as if “Achy Breaky Heart” had its own dance with unique hand gestures signifying homage to the mullet, and all of Toby Keith’s songs would include a simulation of giving Karl Rove a blowjob.

Para Para Max: The Moves 101 slowly leads the viewer through four songs performed by pop star Yoko Ishida. The dance instructors, Mike and Randy, take turns breaking each song down to distinct parts, each with its own terminology.

The first option you can select has Mike and Randy facing the viewer, which makes it slightly confusing when you’re trying to learn the moves and have to remember when it’s time to use the right arm and when it’s time to use the left. Fortunately, they also offer a mirroring option. Getting the arms right is important if you’re going to bring your mad Para Para skillz to a club, but since my performance was going to be restricted to my living room, I didn’t really care.

We popped in the DVD and tried to learn the first featured the techno pop song “A Cruel Angel’s Thesis.” I stood in the middle of the group, with the three-year-old on one side and the six-year-old on the other. We worked on the moves for about an hour, with a lot of rewinding and repetition, and let me just say this: OUCH.

Oh my god. Ouch.

An hour of holding your hands up over your head and waving them around in different patterns hurts. The kids did a lot better than I did, of course, but for me it was a serious upper body workout. (The lower body gets toned with low impact aerobics, since in Para Para dancing, you either don’t move your feet, or you limit yourself to stepping side to side.) Don’t believe me? Try this first lesson.

When Steve came home from work, we all lined up and made him sit next to the TV, (to better keep an eye on the Para Para Dancing Girls) and performed our “Cruel Angel’s Thesis” dance moves for him. He was a very appreciative audience, I must say, even though he declined an opportunity to watch us again.

The next day when the kids asked if we could do Para Para Max dancing again, I was all for it. I think if I follow the DVD every day for a month, not only will I have the dance moves of a thirteen-year-old Japanese girl, I’ll have the ass of one, too.

________________________

Para Para Max: The Moves 101

distributed by Geneon

DVD, 1996

This review originally appeared at TARGET="_blank">J LHLS.

Saturday, June 10, 2006

The Ticking.

There’s this really great scene in the remake of The Fugitive, where we’re introduced to Tommy Lee Jones’ big cheese U.S. Marshall character for the first time. He gets out of his car and walks quietly up to the scene of Harrison Ford’s latest escape. The officer in charge on the scene is frantic, running around and barking at people and letting everyone, including Tommy Lee Jones, know that he is someone very important indeed.

“Just wait just a second,” he snaps when Jones approaches him to introduce himself.

Jones blinks briefly, then in as mild a tone as possible, says with amusement, “Okay,” and backs up until the officer finally calms himself down long enough to realize exactly who he’s been so rude to.

Tommy Lee Jones doesn’t have to scream and yell to let people know he's the best in his profession. He’s that good.

I realize this subject has been touched on before, but a lot of people don’t get into comics for the same reason that they're put off by the barking man. Often, the writers create characters that, if it was fanfic written by girls about Buffy, would be called “Mary Sues,” the writer’s larger-than-life, more perfect than perfect alter ego that all the other characters are super-impressed with. Shocked. Awed. Invariably there’s a pneumatic, limpid-eyed female to coo about how gosh, she thinks the hero is wunnnderful. The protestations are so great, the yelling and screaming and chest-beating so over the top, that the story and artwork are totally overwhelmed by the strident cries of attention from the author's penis.

Renee French, then, is the comic world’s Tommy Lee Jones.

I'd thought, when I first started getting offers from publishing houses to review their books, that it would curb the urge to buy my own. It hasn't. Not at all. All it did was make my "To Buy" list longer, because for better or for worse, the books you get sent are not necessarily books you'd buy on your own. Due to the positive buzz The Ticking has been getting, though, it was right at the top of my "To Buy" list. So when my editor at the Lincoln Heights Literary Society offered me The Ticking for review, I leaped at it. From the very first page, it was worth it.

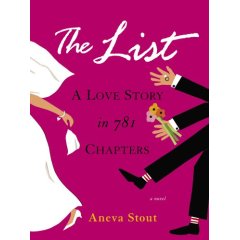

The story tells of the life of Edison Steelhead, a little boy born with grotesque facial deformities that he inherited from his father. I thought Edison and his dad were supposed to resemble lightbulbs, but according to a lengthy interview with the author at Newsarama, it turns out she was going for a more of a fish face.

I was focusing on the "Edison" part of the name and thought "lightbulb," but evidently I was meant to focus on the "Steelhead" part of the name and think "trout."

Fortunately for me, French says in the same interview that she hopes people will find their own personal meanings to her work, so I feel like I  have her permission to compare him to a lightbulb and infer all sorts of lightbulb subtexts in the book that she didn't actually put in there, and cleverly refer to the story as being "luminous" and "enlightening" and such.

have her permission to compare him to a lightbulb and infer all sorts of lightbulb subtexts in the book that she didn't actually put in there, and cleverly refer to the story as being "luminous" and "enlightening" and such.

There are so many complex family themes running though The Ticking, and so many different ways to interpret those themes that it's difficult to describe the depth of such a deceptively simple-seeming graphic novel. Little Edison, whose mother does not survive his birth, is spirited away by his quiet, gentle father to live in a lighthouse. For reasons unstated, Edison and his luminous trout-face (whee!) are hidden away from the public eye by his father, who perhaps is protecting him from cruelty or is saddened and ashamed by him, or both.  Edison spends his time focusing lovingly on sketching slightly grotesque details of human life: dead flies, locks on public bathroom stalls, bits of pubic hair he found left behind on the toilet, covering the first of French's major themes in the novel of accepting the mundane and the ugly as being perfect the way they are. The second major theme, the strife between parent and child, comes when Edison and his father Calvin reach radically different conclusions about their disfigurement. Edison's approach, to embrace his appearance and accept himself for what he is, doesn't sit well with his father, who went through great lengths to change his appearance and encourages Edison to do the same.

Edison spends his time focusing lovingly on sketching slightly grotesque details of human life: dead flies, locks on public bathroom stalls, bits of pubic hair he found left behind on the toilet, covering the first of French's major themes in the novel of accepting the mundane and the ugly as being perfect the way they are. The second major theme, the strife between parent and child, comes when Edison and his father Calvin reach radically different conclusions about their disfigurement. Edison's approach, to embrace his appearance and accept himself for what he is, doesn't sit well with his father, who went through great lengths to change his appearance and encourages Edison to do the same.

When Calvin realizes the extent of his son's loneliness, his response is to bring home a little sister for him, a chimpanzee in a frilly dress. In his growing relationship with the hirsuite Patrice, Edison discovers parts of him that are Calvin-like, namely, his revulsion at Patrice's hobby of eating disgusting things she finds.

This deeply personal story about familial relationships and parental approval strikes a deep chord. It's a struggle to be happy with who you are and what you do if your own family is not happy with who you are and what you do. French, who claims that her own father would prefer that she illustrate greeting cards for a living, (most likely the polar opposite of the creepy little drawings that seem to pour out from her brain to her hand onto the page) writes about this theme gently, but with such sadness and love that it makes The Ticking an incredibly powerful novel. French opens her story with a series of simple pencil sketches of different patterns, consisting of lines and dots. Looking at the sketches gave me the same feeling I sometimes get when looking at a painting in the Art Institute. I love it, I find it riveting, I spend a lot of time in front of it, staring, but I don't know why. And when French begins delving into the story, telling us about the childhood of Edison Steelhead, one of the recurring characters that pops up in her various works from time to time, she somehow manages to send the same underscoring message that she began with those wallpaper-like patterns she drew: study every illustration carefully. Nothing is extraneous. Everything here has been carefully constructed. Because the dialogue is somewhat sparse, it could be said that you could zip through The Ticking in less than ten minutes. To do that would be throwing away the gift French is giving the reader. French has paid her readers the highest compliment of perfecting every word and every illustration before presenting the finished product. It doesn't scream that it's perfect; it just is. Renee French doesn't have to scream. She's that good.

French opens her story with a series of simple pencil sketches of different patterns, consisting of lines and dots. Looking at the sketches gave me the same feeling I sometimes get when looking at a painting in the Art Institute. I love it, I find it riveting, I spend a lot of time in front of it, staring, but I don't know why. And when French begins delving into the story, telling us about the childhood of Edison Steelhead, one of the recurring characters that pops up in her various works from time to time, she somehow manages to send the same underscoring message that she began with those wallpaper-like patterns she drew: study every illustration carefully. Nothing is extraneous. Everything here has been carefully constructed. Because the dialogue is somewhat sparse, it could be said that you could zip through The Ticking in less than ten minutes. To do that would be throwing away the gift French is giving the reader. French has paid her readers the highest compliment of perfecting every word and every illustration before presenting the finished product. It doesn't scream that it's perfect; it just is. Renee French doesn't have to scream. She's that good.

_______________________

The Ticking

by Renee French

2006 by Top Shelf Productions

Hardcover, 228 pp

ISBN: 1-891830-70-8

Sunday, June 04, 2006

It Hit Me Like a Ton of Bricks.

David Rakoff’s back cover blurb of actress Catherine Lloyd Burns’ memoir reads, “Any reader, male or female, who has ever had a mother will be moved and vindicated by Catherine Burns.”

After I read Burns’ debut book chronicling her relationship with her workaholic mother, I thought about his use of the word “vindication,” and concluded that to feel “vindicated,” the work in question must be at least somewhat vindictive in spirit. Inarguably, It Hit Me Like a Ton of Bricks is a vindictive memoir, a cathartic rant against a mother that did not seem to love or support her daughter enough throughout her childhood.

Every slight is remembered: Cathy was left with nannies while her mother traveled the globe with her showbiz executive father, after his death she is warned “not to use [his death] to manipulate others,” she is sent to boarding school while her mother forges a top-notch academic career, she does not feel she has her mother’s approval until she gets cast in a hit TV show (she played Malcolm’s teacher in Malcolm in the Middle), and on and on, until every last stone is thrown.

Halfway through the book, I started getting depressed, and not on Burns’ behalf – I began feeling sorry for her mother.

I’ve made a minor career of refusing to participate in the blasted “Mommy Wars” in any way, shape or form, to the extent that I’ve come under serious criticism for refusing to judge the choices of other mothers. This book is carrying the flag in the Judgment Parade (flag emblem: wagging finger), not only wagging the finger at her mother, but at all parents who don't meet Burns' standards, and as I read it I felt increasingly defensive. My issue, my problem, I know, but there it is. I didn't feel vindicated reading it. Rather, I felt guilty for each time that I indulged in some of my own dramatic mother-blaming. With one notable anecdote involving a young Catherine and the elevator doorman in their building – and the error on her mother’s part here even I must say is unforgivable indeed – I felt the book was turning into a long, protracted adolescent tantrum, and I desperately hoped Burns could manage to stop indulging herself long enough to get over it already.

Which is sort of what happens when Burns begins writing about the birth of her own daughter. In the book’s second part, she begins dropping hints that maybe she’s beginning to understand and accept her mother just a little bit, and by the book’s end, she seems to have reconciled her desire for the non-existent icon of the mother she wants with the actual mother she has, an irritable, flawed human being. Burns begins to communicate with her mother for the very first time and it is then that she realizes the methods behind her mother’s seeming madness, and many of the times she thought her mother was being insensitive, she had simply misunderstood her mother’s motivations.

Olive [Burns’ daughter] and I are in the park with my mother. They are playing peekaboo. Olive is on the wobbly bridge and my mother is underneath looking up through the slats. My mother looks so happy; like a real grandmother. Olive is laughing. It’s a genuine Kodak moment. I look around to see if any of my friends, the other mothers, are here. I want someone else to see how great my life is right now. Olive screams. I turn back around. She has fallen. I pick her up. In my arms I watch her eyes roll back in their sockets, her head go slack, her arms and legs twitch almost rhythmically. This can’t be real, This can’t be happening, I say to myself.

“Olive? Olive what is it? Are you okay? Oh my God, baby, are you all right?” Her eyes are on me, but she is looking through me. She is completely vacant. May daughter is in my arms in another dimension and I can’t penetrate it. I take her to a bench and try to nurse her.

“What’s she doing? Is she eating?” my mother says. I nod.

“What’s she doing? Is she drinking?”

“YES,” I say like I am speaking to a deaf person.

“She’s all right. She’s fine,” she tells me.

“Yeah, I guess so, but that was so weird. She looked like she was having a seizure. It was so scary.”

“She’s fine, she doesn’t even remember. There,” she pokes her.

“She’s fine,” she tells me again. “She’s fine.”

“Well I think I’m going to call the doctor.”

“Nooohh, she’s fine, she doesn’t even remember. Do you? Peekaboo. She’s fine. She’s forgotten all about it.” For some reason this makes me feel neurotic and too emotional. “I’m not afraid she’s traumatized,” I say. “I just want to talk to a doctor. She’s going to bed soon. I want to make sure she doesn’t have a concussion.”

“She’s fine,” my mother repeats, like I am crazy.

Two hours later the phone rings.

“What’d he say? How is she?” It is my mother. “What did the doctor say?”

“He said it sounded like she went into a little bit of shock and was probably fine and if we wanted to be really safe we should go to the emergency room, but he didn’t think that was necessary so he said we should wake her up in a couple of hours and make sure she is ‘rousable.’ Which is excellent since she only started sleeping though the night two weeks ago.”

Eight on the dot the next morning my mother calls.

“How is she?”

“She’s fine.”

“Good. I was so scared.”

“You were?” I say. “Then why did you keep saying she’s fine?”

“Because you were so frightened. I wanted to calm you down.”

“I had no idea you were worried.’

“Of course I was. I was absolutely terrified. But I didn’t want us both to be.”

It Hit Me Like a Ton of Bricks is a memoir guaranteed to bring out strong emotions in the reader. We all have mothers, and it is impossible to read many of the scathing indictments in the novel objectively, without applying the situation to our relationship with our own mothers or, if we are parents, our relationships with our children. If you have an axe to grind with your mother, this book will be a cathartic adrenaline rush to the system. If your mom is your best friend, you may find the reading tough going. And if, like most of us, your relationship with your mother has had its ups and downs, or if you’ve already reconciled your feelings about what your mother may or may not have accomplished with regards to her raising of you, your feelings may be somewhat mixed.

____________________

It Hit Me Like a Ton of Bricks

By Catherine Lloyd Burns

2006 by North Point Press

Hardcover, 225 pp.

ISBN: 0-86547-708-6

Coffee and Donuts.

For several years the foyer of my old apartment building served as a nighttime resting area for two homeless men. As soon as night would fall and the Chicago winter wind would start piercing the flesh and chilling down to the bone, they would show up at our building, settle down onto the chilly ceramic tile floor and sleep in a layered huddle. The foyer was unheated, but as long as they weren’t rousted back out into the elements, they wouldn’t freeze to death. None of us ever had the heart to complain about having to step over their bodies as they snoozed away beneath our mailboxes, and eventually we became attached to them in the way urban people are about the neighborhood homeless – we left gifts of sandwiches and cans of soda next to them for when they woke up, and we worried amongst ourselves on cold nights when we would come home from the clubs and they weren’t there.

Max Estes’ Coffee and Donuts reminded me, just a little bit, of the difficulty of being down on your luck in a city that, either out of necessity or unconcern, has closed its heart against the homeless.

This simply told, bittersweet story gently presents this against-the-odds tale of survival by using two down-and-out anthropomorphized cats, the charismatic Dwight and the silent Jules, who live in a cleaned out dumpster in the alley. Every morning, a kind-hearted anonymous citizen leaves them a breakfast of coffee and donuts. This small kindness is not enough for them to better themselves, and out of desperation the two plan to rob an armored car. Their poorly executed plan goes horribly awry, and by its end both the police and another cat duo – a pair of hardened criminals, these – are after them.

Estes, a grad student at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, tells his straightforward underdog tale as clearly and accessibly as possible. The black and white illustrations are presented on two circular panels per page, with thick lines and obvious details indicating each characters personality: The amiable, mild mannered Dwight wears glasses, and the bad guy wears an eyepatch. The storyline follows Dwight and Jules from their self-inflicted plight and their pursuit by forces both good and bad, right to its inevitable conclusion, with no twists or real surprises.

It is a quietly satisfying little book, appropriate for all ages. My three-year-old, in fact, made off with the book while I was making dinner. I found him in his room, sitting on the bed with it open on his lap.

“Run, kitty cats, run,” he said as he looked at the illustrations.

_________________________

Coffee and Donuts

By Max Estes

2006, Top Shelf Productions

Soft Cover

128 pp

ISBN: 1-891830-80-5

This review originally appeared at TARGET="_blank">J LHLS.

Thursday, June 01, 2006

Consigned to Death.

I have to be honest, mystery novels are not my area of expertise. The only detectives I know well are Encyclopedia Brown and Frank and Joe Hardy, and 25 years have gone by since I read the roughly 91,289 books published about the adventures of the those young sleuths. By now, I’m rusty. Very, very rusty.

Because of this gap in my literary knowledge, reading Jane Cleland’s debut novel Consigned to Death raised more questions for me than it answered. Is this a good mystery novel? Is it a promising beginning to a long series featuring the plucky protagonist, antiques dealer Josie Prescott? How much, exactly, does it help Jane Cleland that she managed to write her mystery without the help of a pet cat? (Actually, I can answer that one: A lot. It helps a lot.)

The premise is this: Josie Prescott keeps an appointment with wealthy businessman Richard Grant to go over heirlooms he planned to sell. She arrives at his home and rings the bell, but no one answers. When sexy police chief Ty Alvarez shows up at her store later in the day, Prescott is shocked to find out that Grant has been murdered, and even more shocked to find out she is the prime suspect.  Armed with her loyal staff, ace attorney Max, and cub newspaper reporter Wes, Prescott swings into action and investigates the crime herself with the hopes of clearing her name. Thrown into the mix are a myriad people who could be suspects – Paula, her sullen employee, Bernard and Martha, her chief competitors in the New Hampshire antiques world, and Grant’s drug addicted daughter Andi, who has a monkey on her back and an axe to grind.

Armed with her loyal staff, ace attorney Max, and cub newspaper reporter Wes, Prescott swings into action and investigates the crime herself with the hopes of clearing her name. Thrown into the mix are a myriad people who could be suspects – Paula, her sullen employee, Bernard and Martha, her chief competitors in the New Hampshire antiques world, and Grant’s drug addicted daughter Andi, who has a monkey on her back and an axe to grind.

The clues trickle in one by one, secrets are discovered, mysteries are either revealed to explain or revealed to expose even more mystery, until the very last chapter, where it all boils down to two essential questions: Will the killer be caught? And will Josie get it on with sexy police chief Alvarez?

Technically, the book does what I assume a mystery novel is supposed to do: Mr. Boddy is found dead in his home, all the clues are carefully examined, and careful questions eliminate suspects. Finally it is revealed that Miss Peacock did it in the library with the candlestick. It’s even got one up on Hasbro, because it’s explained why Miss Peacock cracked open Mr. Boddy’s head.

But is it a good example of the genre? Because I had nothing to compare it to, I didn’t know. I had to check out what other reviewers were saying. Avoiding Amazon’s reader reviews (I assume Cleland’s friends and family liked it well enough), I checked out Kirkus and Publisher’s Weekly. Both gave it high praise; so I have to conclude that if you’re a fan of mystery novels, in particular mystery novels with female protagonists, you may really enjoy Consigned to Death. If, on the other hand, whodunits aren’t your thing, it's unlikely that this is the book that’s going to change your mind about the genre.

_____________________

Consigned to Death

By Jane Cleland

2006 St. Martin’s Press

Hardcover, 276 pages

ISBN: 0-312-34725-1