The Female Thing.

I may be crossing the finish line last in an enormous race of people who have reviewed Laura Kipnis’ latest book, The Female Thing, but I think I can still manage to add something new – a small deconstruction of the cover.

The mostly naked, female form on the cover (love the leaf-as-pudenda motif, by the way) gave me a strong sense of déjà vu, and I went crazy for about a week trying to figure out where I’d seen it before. Finally, it came to me: back in college, my friend Lisa had an old Edgar Winter album, don’t remember which one, but the album’s inside jacket had a photo of a very young Edgar Winter, completely naked, with one hand over his bits. I was simultaneously fascinated and repelled by the image when I saw it, totally appalled that Edgar, who really should never appear naked anywhere at any time, seemed to think it would be a good idea to pose like this and nobody stopped him. Didn’t he have any friends? Did they all secretly hate him?

I have to wonder about the thought process behind putting a female model on the cover of a book about feminism who has exactly the same body as a hairless, anorexic, albino man. Was it deliberate? If so, it certainly backs up Kipnis’ assertion that winds its way through the book – we women are our own worst enemy. Why else would a model with a mostly unattainable body type be used in a book deconstructing the women’s inner battle between empowerment and self-loathing?

Kipnis rather gleefully makes hay with the idea that feminism has reached an impasse, largely due to our own inner battles pitting the skills of femininity – passively manipulating men and circumstances to carve the best niche for ourselves, and feminism – directly attempting to achieve our goals on our own merits.

The book is broken up into four lengthy essays: Envy, Sex, Dirt, and Vulnerability, clearly defining the sticking point barring any further achievements and delineating why women, despite the legal and social gains made through feminism, still feel as dissatisfied as ever, if not more so. While she can dish out the problems, almost daring the reader to disagree, she offers a surprising lack of solutions. In fact, it appears that Kipnis has read one too many women’s magazines in her research and now has an almost pathological aversion to giving advice, branching out only once in support of Soft Scrub bathtub cleanser. No, really. Rather, Kipnis seems to want this book to become the start of a conversation, rather than the end solution, which is fine.

“Envy” describes how progress in the workplace leaves women to finally have the same careers as men, but not particularly enjoying them, as well as depressingly describing how women entering the workforce was used to lower wages for men and women both. Think about Wal-Mart outsourcing to China for cheap labor over more expensive American workers and you’ll get the idea.

“Sex” describes what Kipnis refers to as the “cruel joke” of women’s short end of the stick when it comes to sexual satisfaction, not to mention getting stuck with pregnancy and childbirth. Kipnis takes particular issue with the location of the clitoris, presumably the major spot of sexual pleasure for women (although she and Freud, whom she repeatedly quotes, wonders if that is so, as it seems to have fallen in and out of vogue)* Why, she wonders is the clitoris so far out of the way that most women do not climax through traditional penetration?

Personally, I’m kind of happy it is where it is, safe and out of the way of episiotomies and vaginal tearing during childbirth. But that’s just me. There also seems to be, thanks to a tremendous industry largely fueled by women, an emphasis on having sex “the normal way” or “the right way,” regardless of whether that particular way works for the individual woman.

“Dirt” is a charming history reflecting why women have gotten stuck doing the majority of the housework, blending women’s traditional reputation as being dirty or “unclean” (thanks, Religion!) with why we can’t seem to ignore dirty dishes in the sink.

Kipnis saves the best for last with “Vulnerability,” a potentially controversial piece about how the foundation that structures most women’s behavior is the fear of rape. Given the statistics that she analyzed, she feels rape is not as common as we are lead to believe – not the stranger rape that keeps us in our homes late at night and away from empty parking garages – and maybe we are living in fear for no reason.

My favorite part of “Vulnerability,” and I’ll go so far to say this was my favorite part of the whole book, was Kipnis’ criticism of Andrea Dworkin. Now, I’m a pretty solid old-fashioned liberal feminist – cut me and I bleed Janeane Garofolo's blood - when Kipnis started in on Dworkin I was afraid she was going to move into territory that would ruin the whole book for me. The majority of what I read about Dworkin, when not written by a radical feminist, is reactionary and contains more than a little streak of vindictiveness in it, railing away at things Dworkin never said. That old chestnut "Dworkin said all sex was rape!" chestnut that, despite being thoroughly debunked by Snopes, keeps floating like a rotten egg to the surface of popular culture, like the belief in Spontaneous Human Combustion or Creationism.

So I was delighted to read a critical essay of Dworkin's philosophies that managed to strongly disagree with what Dworkin has actually said, while being respectful of both Dworkin and her body of work.

Although I would be surprised if radical feminists enjoy The Female Thing as much as I think liberal feminists will, Kipnis is actually similar to Dworkin in that, whether or not you agree with their conclusions, they both produce work that challenges you to think about feminism from different angles, ultimately providing many more questions than answers.

______________________________

*Part of the problem with the mystery surrounding women’s joy buzzers is the fact that until last year, nobody had bothered to map out the nerve endings in women’s sexual organs, often cutting right through them during hysterectomies. Fortunately, a woman scientist, apparently not particularly held back by Envy, is mapping everything out for us as you read this, and hurray for her.

The Female Thing

by Laura Kipnis

October, 2006 by Pantheon Books

Hardcover, 173pp

ISBN: 0-375-42417-2

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Tear Down the Mountain.

It looks like I missed author Roger Alan Skipper’s reading of his debut novel Tear Down the Mountain at Malaprop’s Bookstore earlier this month. I’m sorry I missed that reading, because Malaprop’s, a top notch independent bookstore nestled in the Appalachian Mountains in Asheville, North Carolina, is the perfect place to curl up in a chair and listen to Skipper’s story of a struggling West Virginia romance.

It’s easy to lose yourself in a novel about life in the Appalachian Mountains when you’re in Appalachia yourself, but with Tear Down the Mountain, although it would be ideal, it isn’t really necessary, as Skipper has recreated rural mountain life so precisely it’s as if you’re living life right alongside the characters.

We first meet Janet Hollar and Sid Lore as teenagers struggling with loneliness and alienation; Janet because she is unable to lose herself enough in her Pentecostal religion long enough to speak in tongues, and Sid because he won’t try. When circumstances threaten to keep them apart, they decide to marry, and what follows is the decades-long chronicling of their marriage and their struggle to survive with very few resources – no education, no jobs, no family and very few friends to lean on for support. At the start of their marriage, the pair only have two assets – their youth and their hope, both of which trickle away as poverty begins to grind them down.

Early in their marriage, Sid ruins his back doing manual labor as a mason, and Janet must support them as a flagger for a paving crew. As Sid takes over the duties of cooking and cleaning their silver single-wide trailer, his frustration and feelings of emasculation grow, and Janet’s well-intentioned but horrid anniversary gift to him, an apron, only make things worse. Finally, he can’t take any more and insists that they need to leave West Virginia, to “tear down the mountain” and go somewhere with opportunity. The pull of Appalachia is too strong in Janet, and the fight that ensues shatters what is left of their hope, manifested by shards of Sid’s teeth and Janet’s only flower pot.

Roger Alan Skipper writes about his home state in the grand tradition of the great Southern writers. What Eudora Welty is to Mississippi and Harper Lee is to Alabama, Skipper is to West Virginia. His descriptions of modern rural life are almost tangible. Early in the novel, Janet’s disapproving father goads Sid into going hunting with Harlin Wall, a dangerous and unstable man. Sid goes to Harlin’s house, a “swayback two-story structure” that is tucked so far back in the hollow that Sid can’t believe anyone really lives there. The door is open, and when Sid pokes his head in to announce his presence, he is greeted with a scene so grotesque and horrific it was “too much to look at, yet every detail impossible not to see.”

This was the strongest part of the novel by far because it isn’t every romance book that takes a completely unexpected swerve into the horror genre. And best of all, in this brief interlude into Creepyland, Skipper does what hundreds of horror novelists never manage. By underpromising – Going to Harlin Wall’s? Oh, you don’t want to do that – and overdelivering, he gives the reader a moment of genuine eye-popping horror, a completely realistic depiction of rural poverty that for the unprepared like Sid, is blindingly awful and unforgettable.

Tear Down the Mountain casts an unsentimental view of rural poverty, showing the grinding down of isolated rural life combined with humanity’s remarkable ability to persevere, like weed sprouts pushing up through concrete.

And while I’m sorry I missed the reading at Malaprop’s, I’m glad the book made its way out of Appalachia to a wider audience.

________________________________

Tear Down the Mountain

By Roger Alan Skipper

September 2006 by Soft Skull Press

Softcover, 208 pp

ISBN: 1-933368-34-9

Thursday, November 16, 2006

José Guadalupe Posada: 150 Years

Everyone who celebrated the Mexican holiday Day of the Dead last November 2 owes a debt to José Posada. The 19th century printmaker’s etchings of creepy but playful skeletons, or calavera, are such a common household decoration it can be difficult to remember that they had an original creator.

José Guadalupe Posada’s artwork was pervasive in Mexico in the 19th century. At his peak, the peasant-born, working class Posada illustrated text for 12 newspapers, as well as issuing broadsheets, sensationalized handouts that played up the general public’s taste for the lurid, describing in breathless detail murders, grotesque births, and sightings of the devil, as well as poking fun at corrupt political figures. In fact, Posada’s use of skeletons to represent corruption predates more well-known expressionists.

Although somewhat unknown in the United States, there has recently been a revival of his work in Mexico. Artists such as Diego Rivera have cited Posada as a primary influence, and at last his work has begun to be elevated from commercialized folklore to the respect it deserves, and his influence in shaping modern Mexican art is acknowledged.

Posada did face obstacles to getting critical acclaim for his work. Then, just like now, there was a tendency to dismiss popular cartoonists as not being serious artists. European art was considered the standard of fine art, and most Mexican artists emulated their style rather than embracing the aspects of their culture and creating a unique style that is distinctly Mexican. Posada was the first to do this.

Still, the influences of European art are still present in his work, giving his etchings the feel of an Edward Gorey sketch crossed with Medieval European Catholic art. The result is often so deliciously creepy that to this day Posada wipes the floor with any Goth.

Editor Artemio Rodríguez's choice to group Posada's etchings into thematic categories gives the reader a chance to see the evolution of his printwork, from the earlier etchings to his later years, when the detail of his work is breathtaking. Page 77 shows a cartoony etching of a man and woman embracing. The characters are very simply drawn, and it seems the triumph is in creating the work at all rather than the work itself. In contrast, an etching on the same theme done in later years on page 73 is quite different. The man's hand is gently guiding the woman's lips up to his, her body is leaning toward him, and his other hand is curled tenderly around her waist. Looking at it, you forget how difficult the creating of it actually is, and are able to focus solely on the passion leaping off the page.

His portrait of a circus actress (page 98) takes the art of European portrait painting, at its zenith in the 19th century, and turns it into a purely Mexican creation. The result is arresting, proving that Posada is indeed worthy of serious critical acclaim. His preternatural talent for drawing out the core of humanity in all his artwork, be it dancing calavera or a monk riding a bike, may have given strength to the popularity of the broadsheets. As fantastical as the text was - the book is bilingual, showing the original text with an English translation next to it - his illustrations often contained an essential truth.

Despite the popularity of his work, José Posada died in poverty in 1913, at the age of 61, his body unclaimed. He was buried in a pauper's grave in the Cemetery of Dolores, only to be exhumed seven years later and thrown, anonymous and unloved, into a common grave. Such an insult to the artist whose work arguably had the greatest impact on the Day of the Dead, a holiday devoted to honoring those who have passed.

But maybe, with the renewed interest in Posada's work, the honor will come when anthologies such as José Guadalupe Posada: 150 Years are studied and admired for the revolutionary artwork within.

________________________

First posted at the Journal for the Lincoln Heights Literary Society

José Guadalupe Posada: 150 Years

Artemio Rodríguez, Editor

2003 by La Mano Press

Softcover, 126 pp

ISBN: 0-9724735-0-5

Sunday, November 12, 2006

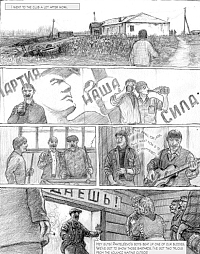

Siberia

O Comrades! I have fallen in love with another bleak graphic novel about living in a Totalitarian regime. Let the relentless urging for everyone to read it begin again!

Although not as weird as life depicted by my boyfriend* Guy DeLisle’s best comic evar, Pyongyang, Nikolai Maslov’s Siberia is definitely more grim. While DeLisle knew his time in Pyongyang would come to an end, only a few months spent in the world's last Communist country, he was able to maintain a humorous, wry detachment from life in the shadow of Kim Jong Il’s bouffant. Maslov’s perspective, however, is that of someone born and raised in pre-Perestroika Siberia, with very little hope of escaping the hammer and sickle.

There is a common Russian expression, “When you’re part of a flock, it doesn’t matter who’s first and who’s last.” With such a motto of resignation adopted by his countrymen, what is most amazing about the book is Maslov’s seemingly unflagging determination that no matter what, he would never stop trying to be first. It reminded me of the old Far Side cartoon with millions of identical penguins milling around, and in the middle of the crowd, one rises up, wings upraised, singing, “I’ve just got to be me!”

And after almost half a century of struggling to break out of the endless cycle of poverty and depression to become an artist and create something genuinely beautiful, he did it.

Siberia is a graphic novel written by a nearly lifelong resident of Siberia, a middle-aged night watchman who had never even seen a graphic novel when he picked up his pencil and began to draw.

“My story is neither the most violent, nor the most tragic,” he writes, and as his life unfolds, the image of millions of people living an entire lifetime with no real hope is almost overwhelming. His story begins in 1971, in Western Siberia, and from the very first pencil sketch, showing a desolate strip of road surrounded by log cabins in the mud, an image right out of 19th century Chekov, the strong desire to escape from such a place is evident. With the blackest of humor, he shows himself in school, listening to his teacher tell the students, “…Thanks to the guidance of the Communist Party, we live in the world’s richest country.” Then he contrasts the reality of Siberian life, sketching his young self watching miserably, as unhappy men succumb to their only passion, vodka, while he wonders when he would take his place among the same unhappy bar patrons.

His story begins in 1971, in Western Siberia, and from the very first pencil sketch, showing a desolate strip of road surrounded by log cabins in the mud, an image right out of 19th century Chekov, the strong desire to escape from such a place is evident. With the blackest of humor, he shows himself in school, listening to his teacher tell the students, “…Thanks to the guidance of the Communist Party, we live in the world’s richest country.” Then he contrasts the reality of Siberian life, sketching his young self watching miserably, as unhappy men succumb to their only passion, vodka, while he wonders when he would take his place among the same unhappy bar patrons.

Siberia is drowning in vodka. It is the only thing the rural Soviets felt they had to live for. In a particularly striking moment, Maslov shows two panels, the first of a store, its shelves nearly empty, worn boots lined up next to four sauce pans. The next panel is that of a woman, mouth open with joy, holding a bottle of vodka in each hand. Behind her are hundreds of gleaming vodka bottles wedged tightly together on brightly lit shelves. The message is clear: there is nothing else here.

From his compulsory service in Mongolia, Maslov only dreams about a few moments of escape from his life of servitude, going AWOL from time to time to explore the mountainous countryside and willing taking the 40 days of solitary confinement as punishment just for the chance to indulge his yearning to be free. These moments of escape are when he allows himself to show the wild beauty of his homeland, and his love and loyalty to his country shine through. In a gorgeous sketch of the sun streaming through the trees, he manages to make the pencil gray seem blindingly bright. During his service, instead of trees, he draws sausages on propaganda posters. “The only place we ever saw them,” he remarks dryly.

After his discharge, he heads to Moscow where he can at last attend art school, only to learn that his lack of political connections will not get him very far. He also learns that in Moscow, getting far as an artist means a lifetime of showing “the great advantages of the Soviet way of life.” Great, more sausages.

Despite the unrelenting hardship of his life, Maslov approached a Soviet publisher in 1996 and showed him 3 pencil sketches. Shyly, he pitched his book. After reviewing the sketches, the publicist took an almost unheard of chance on Maslov and paid him an advance, allowing him to quit his night watchman job for three years and tell his life story. When it became published internationally, first in France, now in the United States, Maslov flatly refused to believe it was true.

Perhaps because of his lifelong struggle to stand out among the millions and have his story finally told, the lesson Maslov seems to want to get through is this:

“…what you have to look for in life is truth and kindness. Otherwise, what’s life for?”

__________________________

*I have many, many boyfriends, none of whom have ever met me.

___________________________

Siberia

By Nikolai Maslov

Translated by Blake Ferris

2006 by Soft Skull Press

ISBN: 1-933368-03-9

Saturday, November 11, 2006

Bridge to Terabithia

Note: There are spoilers in this review, and although I feel slightly silly saying this, like I'm protecting you from the secret of Citizen Kane, you have been warned: Here be spoilers.

I still have my copy from childhood. It's in the family room, on the bookshelf I've reserved to hold my old books for the kids when they get old enough to read them. The Harry Potter series squats solidly in the middle next to the Narnia Chronicles. The Neverending Story is there, as is Phillip Pullman's Dark Materials and the first volume of Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events. Bridge to Terabithia is in the far right corner, almost at the end, pushed away to one side between Grimm's Fairy Tales and a book written by my high school English teacher Idella Bodie.

Every now and then I take it out and look at it, wondering if Alex is ready yet. And every time I've put it back on the shelf unread. I don't know if Alex is ready or not. I know I'm not ready. I'm not prepared to chip away at his innocence quite yet, to let him to absorb the lesson that Katherine Paterson teaches in this incredible book, arguably the greatest children's book ever written. The lesson is harsh. It's shocking, cruel, even. Bridge to Terabithiais the book where so many kids in my generation learned the reality that life isn't fair.

Tonight Alex and I read one of Barbara Parks' Junie B. Jones books. In this particular story, Meanie Jim has a birthday party and invites every kid in the class except for Junie B. And it hurts. And as she tries more and more flamboyant ways of finagling an invitation, the more determined Meanie Jim is to hurt her feelings. In the end, Junie doesn't go to the party. But only after Meanie Jim's mother finds out that he's been withholding her invitation. The whole class was to be invited, Junie B. included. However, she decides to stay home fixing the upstairs toilet with her grandpa, because the party has somehow lost its appeal.

You can empathize with poor Junie B., certainly. At one time or another, all kids have been bullied or excluded. But the wacky antics of Junie B. coupled with the cartoony illustrations in the book leave the young reader feeling a bit detached. I'm sorry, Junie B. That's too bad. Life's not fair.

Bridge to Terabithia plays out a little differently. It isn't just the characters who discover that life isn't fair, it's also you. You cry. You ache. You flip frantically through the pages in disbelief, muttering, no, no, it can't happen like that, it can't. But it does. Paterson strips away the wall of detachment between reader and character in the rawest of all possible ways, and she doesn't seem to care if you resent her for it, because after all, we often resent our greatest teachers.  The story begins, as most children's stories do, with a boy. Not a rich boy. Not a popular boy. Not a boy who is charming or particularly smart or curious or funny. Just a boy, Jesse. And Jesse really only wants two things out of life - he wants the attention of his hippie music teacher who has the face of an angel, and he wants to be the fastest boy in the fifth grade.

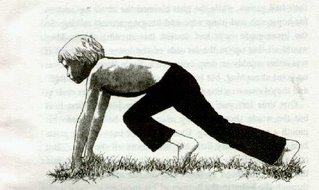

The story begins, as most children's stories do, with a boy. Not a rich boy. Not a popular boy. Not a boy who is charming or particularly smart or curious or funny. Just a boy, Jesse. And Jesse really only wants two things out of life - he wants the attention of his hippie music teacher who has the face of an angel, and he wants to be the fastest boy in the fifth grade.

Every morning he wakes up before the rest of his family begins their day, and he runs around the pasture on their farm, pushing himself as hard as he can. He runs to forget the loneliness he feels within his own family, he runs to make his father, a long haul trucker often on the road, proud. He runs to impress the music teacher, Miss Edmonds. He runs to hide his secret love of art and music, a secret that would earn him the reputation of being a sissy. He wants to be the fastest, so what he is inside can be hidden by what is seen on the outside: The Fastest Boy in the Fifth Grade. His fame will make him invisible, safe. And then one morning right before the school year begins, during his last early practice run in the pasture, he meets Leslie.

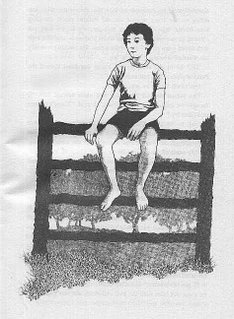

If you're so afraid of the cow," the voice said, "why don't you just climb the fence?" He paused in midair like a stop-action TV shot and turned, almost losing his balance, to face the questioner, who was sitting on the fence nearest the old Perkins place, dangling bare brown legs. The person had jaggedy brown haircut close to its face and wore one of those undershirtlike tops with faded jeans cut off above the knees. He honestly couldn't tell whether it was a girl or a boy.

He paused in midair like a stop-action TV shot and turned, almost losing his balance, to face the questioner, who was sitting on the fence nearest the old Perkins place, dangling bare brown legs. The person had jaggedy brown haircut close to its face and wore one of those undershirtlike tops with faded jeans cut off above the knees. He honestly couldn't tell whether it was a girl or a boy.

"Hi," he or she said, jerking his or her head toward the Perkins place. "We just moved in."

Jess stood where he was, staring.

The person slid off the fence and came toward him. "I thought we might be friends," it said. "There's no one else close by."

Initially, Jess rejects Leslie's overtures of friendship. She doesn't look right, she doesn't dress right, she seems peculiarly unconcerned with how she comes across to the other kids, and worst of all, she's better at being a boy than all the other boys. On the first day of the races, Leslie insists on joining in. To the boys' dismay, Jess included, Leslie wins all the heats in a blowout. She makes it look like she's not even trying.

She ran as though it was her nature. It reminded him of the flight of wild ducks in the autumn. So smooth. The word "beautiful" came to his mind, but he shook it away...

As she turns and stands, smiling, at the finish line, the boys' resentment nearly takes her breath away. Stupid weird Leslie. She ruined everything. She just doesn't know how to act right.

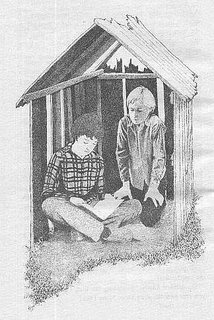

Things get worse for Leslie. She's too smart. Her eyes shine too brightly. And most shockingly, her family doesn't own a TV. As the mockery of Leslie increases, Jess begins to feel protective of her. Soon they become friends, and as their friendship grows, Jess realizes that the angel isn't Miss Edmonds; it's Leslie. Jess succumbs totally to Leslie. She becomes the most powerful presence he's ever known. She lifts him up from the despair of his poverty-stricken rural world and offers him hope, salvation, and the possibility of freedom. She encourages him to aspire for more than just survival. They become soul mates. Deep in the woods they hide, swinging over the craggy ravine on a rope, Tarzan-like, to reach the pine forest, where the trees grew thick at the top and the sun shown through like a veil. Here Leslie and Jess create a magic world, Terabithia, for just the two of them. Here, Jess can play and draw and laugh, away from the judgment of his family and his peers.

Jess succumbs totally to Leslie. She becomes the most powerful presence he's ever known. She lifts him up from the despair of his poverty-stricken rural world and offers him hope, salvation, and the possibility of freedom. She encourages him to aspire for more than just survival. They become soul mates. Deep in the woods they hide, swinging over the craggy ravine on a rope, Tarzan-like, to reach the pine forest, where the trees grew thick at the top and the sun shown through like a veil. Here Leslie and Jess create a magic world, Terabithia, for just the two of them. Here, Jess can play and draw and laugh, away from the judgment of his family and his peers.

As soon as it becomes clear that Leslie is the embodiment of religion, Paterson does the unthinkable: She proves there is no God.

I remember finishing this book as a child, not much older than Alex is now. Tears streaming down my face, crying, "It isn't fair! How could this happen? How could this happen to me?"

There wasn't a detached musing about the events in the book. The pain I felt was raw and real, and hit me harder than any book ever had. Jess and Leslie weren't cartoon characters. They weren't zany and funny and they didn't get into crazy, mixed-up scrapes. They looked and acted like real kids, with real concerns and dreams. They could have been anybody I knew, and when I realized that, I was horrified. I took it very personally. It wasn't even until I was an adult that I accepted the ending of the book. In my resentment toward Paterson, I never noticed how neatly she sews up the ending, that his newly-found passion and strength win the respect of his aloof father more than winning a fifth grade race ever could, and most importantly, by opening his mind and heart Jesse discovers that salvation lies within himself.

It wasn't even until I was an adult that I accepted the ending of the book. In my resentment toward Paterson, I never noticed how neatly she sews up the ending, that his newly-found passion and strength win the respect of his aloof father more than winning a fifth grade race ever could, and most importantly, by opening his mind and heart Jesse discovers that salvation lies within himself.

I can pick up on those more subtle lessons now, and all the social, political, and class issues Patterson peppers thoughout the book that lie in thick layers, like the needles carpeting the floor of Leslie's Pine Forest.

I just can't drop Bridge to Terabithia on my babies like an atom bomb. I discovered it myself at the library when I was eight or nine, and I think the independent discovery of such a profound novel was what caused it to be the most influential book of my childhood.

I'm going to slip it back quietly onto the shelf now, and leave it alone. Someday, when the boys are ready, it will be waiting for them.

________________

Bridge to Terabithia

by Katherine Paterson

illustrated by Donna Diamond

Harper Classics

Reissue edition 1987

ISBN: 0-064-40184-7

Thanks to Hennessey Catholic College for uploading Donna Diamond's original artwork.

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Cycle Savvy: The Smart Teen’s Guide to the Mysteries of Her Body.

There seem to be four ways of going about educating teenagers about sexuality:

1.) Shaming them and filling them with fear and misinformation. This method, called “abstinence only education,” is currently splitting all the government grants allotted for sex education with phony abortion clinics.

2.) Ignoring the problem by being too freaked out to talk to your teenager or by being generally unapproachable. I have no data for this, but suspect it’s a more common method than one would hope.

3.) Giving them the go-ahead to do anything, anytime, with anyone. Although Planned Parenthood, liberals, hippies, and feminists usually get the credit for coming up with this plan, it has not yet been proven to actually exist as an educational method.

4.) Giving the teenager solid, factual, medically-based information about the reproductive workings of the human body, then presenting options for controlling reproduction in a clear, non-judgmental way, as well as thoroughly going over peer pressure, sexually-transmitted diseases, and the effectiveness of various birth control methods at preventing both pregnancy and STDs.

The last method is the one I most approve of, and happily, it’s the method used in Cycle Savvy: The Smart Teen’s Guide to the Mysteries of Her Body.

Toni Weschler, author of the successful Taking Charge of Your Fertility, is back, this time with a book teaching teens how to chart their ovulation cycles. In Cycle Savvy, Weschler firmly stresses that charting fertility is not to be used as birth control for the teen set. Rather, she encourages young women to pay attention to the rhythms of their bodies, pitching the advantages of being accurately able to predict when the teen will get her period, when she’ll get PMS, and when she’s ovulating. Being in tune with your body, Weschler posits, is a great, even essential way to generate self-respect in the teen girl, and self-respect, in turn, is the best method of birth control there is.

If the teen chooses to have sex anyway, Weschler provides a strong argument for condom use as an absolute must-have, wisely pointing out that if a boy does not care if he gets you pregnant or gives you an STD, you shouldn’t be having sex with him.

Equally valuable are the appendices she provides with a complete rundown of the most common STDs as well as valuable information for health resource contacts such as Planned Parenthood, the STD Hotline, and the Emergency Contraceptive Hotline, and numerous websites devoted to aspects of teen sexuality and education, (including one of my favorites, Scarleteen

Weschler has a very personable, easily accessible style, and in between the medical information gives plenty of anecdotes from women telling stories that range from the embarrassing to heart-warming. Additionally, she peppers the book with fun quizzes and crossword puzzles.

Not having any teen girls of my own, and not seeing any coming in the foreseeable future, I loaned the book to my cubicle neighbor at the large company where I work.

Like many Orange County natives, she leans a little to the right (and admitted that so far she was leaning toward Option 2 on my methods of sex ed list.) So I thought she would be a good balance for my Option 3 ways.

“I really like this book,” she said. “I like the way everything is so factually laid out and the information is so specific and clear. I would definitely give this to my daughter.

“And discuss it with her,” she added.

_______________________

Cycle Savvy: The Smart Teen’s Guide to the Mysteries of Her Body

By Toni Weschler, MPH

September, 2006 by Harper Collins

Paperback, 205 pp

ISBN: 0-06-082964-8

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Sakura Taisen, Volume 1

So, this is Manga. I’ve heard of it, but I’ve never read it before, or even seen it, and didn’t know you read it back to front and right to left. But ignorance has never stopped me from doing anything before, so on with the review!

Sakura Taisen, or “Cherry Blossom War,” is a cute enough story, and seems aimed at the young teenage set. The scene is set in Tokyo, in 1921. Ensign Ogami, a young Navy man, is given what at first blush appears to be a demeaning, insulting assignment: he is relegated to a theatre, and forced to work as a ticket taker. Surrounded by spoiled young actresses all day, he grows increasingly grumpy, feeling like his talent as a soldier is being wasted. During his stay at the Grand Imperial Theatre, he notices that the young ladies, acting skills aside, not only seem to be proficient at weaponry, but occasionally show the ability for telekinesis as well. And there’s also the obligatory village getting attacked by monsters and giant robots, too.

So, it’s cute enough, and quite readable, but since I was reading it primarily for review purposes and not as a Manga fan, I felt like it was a waste of time. While researching the book, I found that it was created by Sega, and the Sakura Taisen line is not only a Manga series, but started off as a video game, and became a live action stage show, produced dozens of top-selling CDs, a tv show, and a line of snack food products. Although the Disney corporation attempts the same sort of product marketing with their young stars such as Hilary Duff, they can only dream of this sort of mass-media saturation that the Tokyo-based companies have done.

As with almost all popular culture, I mostly don’t get it, and with Manga – at least, this particular Manga, I found it kind of depressing. Sega doesn’t care if I like this Manga book or not. They’re not calibrating their level of success by any sort of artistic merit. They’re gauging their success by their profit margin, and their gross sales indicate they’re very, very successful indeed.

The Manga parade is going to march on without me; in fact, I’m about the equivalent of a bacterium perched on their ear – they won’t even know I’m there.

Good story, bad story, read it, don’t read it, it doesn’t matter. Sega won’t care.

_________________________

Originally posted at the Journal for the Lincoln Heights Literary Society

Sakura Taisen

Story by Ohji Hiroi

2005 by TokyoPop

Paperback, 184 pp.

ISBN: 1-59816-484-4

Friday, November 03, 2006

24-Karat Kids.

Oooooooh, check out this cover, will you? Bright shiny red with flashy gold cursive. Retro-chic ladies on the cover that look like they waltzed off the credits of some Rock Hudson-Doris Day movie. So light! So airy! So Nouveau York! This cover tells you exactly what kind of book this is going to be and exactly how you're going to feel while reading it.

This kind of flawless presentation can only mean one thing: Olga Grlic is in the house.

She designed the other cover that I adored, the What Do You Do All Day cover that I loved so much more than I loved the book itself. And again, thanks to Grlic, the outside has outshown the inside. I don't know whether that's a good thing or a bad thing, but I don't care. I'm starting an Olga Grlic fan club. A fan club of one, maybe, but a fan club nonetheless, and I will sit here in my chair and wave my giant foam finger until Grlic gets the respect she deserves.

So what does Ms. Grlic teach us about 24-Karat Kids? What expectations does she give us?

From the cover, one would think it is light. It is gossipy. It has a female protagonist, most likely a fashionable young New York pediatrician with wealthy clientele. It promises to spill the beans on New York's elite Mommies, and you'll have a front row seat.

And that is exactly, exactly what you get.

Dr. Shelley Green is a New York pediatrician who is just setting up practice at Madison Pediatrics, the upper-East side clinic with super rich clientele. She has a fabulous new job, she's losing weight, she's shopping, she's thinking of ditching her reliable, but slightly stodgy fiance for an Old Money hottie, and best of all, she's got dozens of stories to tell about the hypercompetitive world of the Upper East side mommies.

Although the book promises to be an insider's scathing look into the world of the New York elite, a la The Devil Wears Prada and The Nanny Diaries, 24-Karat Kids has a much softer, less cruel approach to its subjects, perhaps because author Dr. Judy Goldstein is a pediatrician still in practice on the Upper East side, and she's learned from the mistakes of Truman Capote, or she and co-author Sebastian Stuart have a little age and wisdom under their belts, and can tell all without hurting anybody's feelings. Goldstein and Stuart write about parents who hire a math tutor for their 8-month old, parents who want to run a battery of tests on their 14-year-old son when they catch him eating a Big Mac, and a very sick little girl with a recently deceased mother, whose high-power Daddy will not take time off work to take his girl to the doctor, and they manage to do it all without sounding overly judgemental or cruel. Between the stories, Dr. Green shops, loses weight, and goes a little boy crazy. Before the middle of the book, you can already predict exactly how all the plot points are going to resolve themselves - and you'll be right. There isn't a single surprise in the book, not one errant idea that leaps out and startles the reader.

But that's okay, if you feel like enjoying a book but are too tired to give it your full concentration. Goldstein and Stuart have created a piece of air-popped popcorn, something to snack on and enjoy without actually filling yourself up.

________________________

24-Karat Kids

by Dr. Judy Goldstein and Sebastian Stuart

June, 2006 by St. Martin's Press

Hardcover, 292 pp.

ISBN: 0-312-34327-2