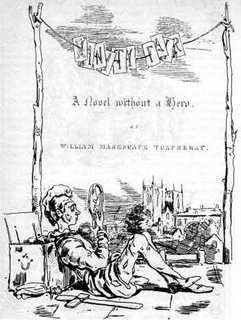

Vanity Fair.

It seems I got stuck inside an endless book again. The last book, Jung Chang's Mao, ate up all of September and a considerable amount of October, too. After I'd finally read the last page, I closed the book, and put it back on the shelf, and then spent the next week staring at it suspiciously, like it was going to leap out of its jacket, open itself and glom onto my face, shrieking, "I'm not finished yet! Only 4000 more pages to go!" This Winter belonged to Thackeray's satirical classic Vanity Fair, and I can see it right now in the corner of my eye. I can't prove it, but I think it may be inching its way toward me.

I never used to have this kind of problem with books, but then again, I never used to have kids and a husband, either. I blame them entirely. It's their fault, theirs, and maybe the dogged determination I've developed to finish a complex book that might be better appreciated by someone who has concentration skills that are better developed, or a quieter, less demanding family.

I mean, I finished the book today, reading the last few pages while, and I am not making this up, literally fighting off my children, who were taking turns leaping on me and using me as a human trampoline.

Forgive me if I may not have fully absorbed all the nuances of Thackeray's masterpiece, but at least I got the basic plotline down.

The sad thing is, when I had a chance to sneak away and read a chapter upstairs, locked in my bedroom, the book was brilliant. It was brilliant, but the way things were going I was only reading one page every three days. And you know, it was almost a 700 page book. Clearly this would not do, so I had to sacrifice a certain amount of comprehension in order to finish it.

The story follows two girls, the cunning Becky Sharp and the personality-free Amelia Sedley around the turn of the 19th century. Becky, the daughter of an artist and a French actress, met the middle-class Amelia at a girls' school where Amelia was a regular student and Becky a charity pupil. For the entirety of the book, we watch the artful and witty Becky use every weapon in her arsenal to claw her way to the top, employing traditional feminine wiles, fraud, illegal gambling, and possibly murder to get there. Amelia, on the other hand, was identical to a glass of warm water. Sometimes the water was in an impoverished home, sometimes it was in a mansion, sometimes it was riding in a carriage, it made no difference because the glass of water never, ever changed or noticed anything around it. Amelia drove both Becky and me crazy; Becky because she actually had to interact with her to get what she wanted, me because I don't want to read 400 pages about a glass of water.

Because my powers of concentration were drained by small, often obnoxious children, I can't really tell what Thackeray was really thinking about either of his young creations. On one hand it seemed that he kept mentioning how much men loved Amelia, and women who disliked her were just jealous, crap we've heard a million times and never, ever stops being stupid, but on the other hand it seemed possible that he was mocking the idea. I don't know! I couldn't tell! Somewhere toward the middle of the book I gave up trying to figure it out.

Given that Vanity Fair is a satire on 19th century attitudes, and made a lot of critics angry with its bleak presentation of humanity - and come to think of it, every single character was riddled with flaws that were never resolved - it seems entirely plausible that Thackeray was contrasting Becky and Amelia to show the unfairness of condemning a woman for getting by on her wit and praising another woman for being a totally mindless, suffering doormat.

I think I would have loved this book if, say, I were on a beach in Hawaii ALL ALONE. I would have come back from my monthlong vacation very tanned, rested, and capable of stunningly intelligent insights on 19th-century satire.

But that didn't happen, damn it, so I have no choice but to leave you with this oratorical blowjob from Charlotte Brontë:

The more I read of Thackeray's works - the more certain I am that he stands alone; alone in his sagacity, alone in his truth, alone in his feeling (his feeling, though he makes no noise about it, is about the most genuine that ever lived in a printed page) alone in his power, alone in his simplicity, alone in his self-control. Thackeray is a Titan.

...and some auto-fellatio from Thackeray himself:

There is no use denying the matter or blinking it now. I am become a sort of great man in my way - all but at the top of the tree: indeed there if the truth were known and having a great fight up there with Dickens.

_______________________

Vanity Fair

by William Makepeace Thackeray

Barnes & Noble Classics

Originally serialized in monthly parts between January 1847 and July 1848

Published in volume form in 1848.

This hardcover edition printed in 2005.

680 pages