Bridge to Terabithia

Note: There are spoilers in this review, and although I feel slightly silly saying this, like I'm protecting you from the secret of Citizen Kane, you have been warned: Here be spoilers.

I still have my copy from childhood. It's in the family room, on the bookshelf I've reserved to hold my old books for the kids when they get old enough to read them. The Harry Potter series squats solidly in the middle next to the Narnia Chronicles. The Neverending Story is there, as is Phillip Pullman's Dark Materials and the first volume of Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events. Bridge to Terabithia is in the far right corner, almost at the end, pushed away to one side between Grimm's Fairy Tales and a book written by my high school English teacher Idella Bodie.

Every now and then I take it out and look at it, wondering if Alex is ready yet. And every time I've put it back on the shelf unread. I don't know if Alex is ready or not. I know I'm not ready. I'm not prepared to chip away at his innocence quite yet, to let him to absorb the lesson that Katherine Paterson teaches in this incredible book, arguably the greatest children's book ever written. The lesson is harsh. It's shocking, cruel, even. Bridge to Terabithiais the book where so many kids in my generation learned the reality that life isn't fair.

Tonight Alex and I read one of Barbara Parks' Junie B. Jones books. In this particular story, Meanie Jim has a birthday party and invites every kid in the class except for Junie B. And it hurts. And as she tries more and more flamboyant ways of finagling an invitation, the more determined Meanie Jim is to hurt her feelings. In the end, Junie doesn't go to the party. But only after Meanie Jim's mother finds out that he's been withholding her invitation. The whole class was to be invited, Junie B. included. However, she decides to stay home fixing the upstairs toilet with her grandpa, because the party has somehow lost its appeal.

You can empathize with poor Junie B., certainly. At one time or another, all kids have been bullied or excluded. But the wacky antics of Junie B. coupled with the cartoony illustrations in the book leave the young reader feeling a bit detached. I'm sorry, Junie B. That's too bad. Life's not fair.

Bridge to Terabithia plays out a little differently. It isn't just the characters who discover that life isn't fair, it's also you. You cry. You ache. You flip frantically through the pages in disbelief, muttering, no, no, it can't happen like that, it can't. But it does. Paterson strips away the wall of detachment between reader and character in the rawest of all possible ways, and she doesn't seem to care if you resent her for it, because after all, we often resent our greatest teachers.  The story begins, as most children's stories do, with a boy. Not a rich boy. Not a popular boy. Not a boy who is charming or particularly smart or curious or funny. Just a boy, Jesse. And Jesse really only wants two things out of life - he wants the attention of his hippie music teacher who has the face of an angel, and he wants to be the fastest boy in the fifth grade.

The story begins, as most children's stories do, with a boy. Not a rich boy. Not a popular boy. Not a boy who is charming or particularly smart or curious or funny. Just a boy, Jesse. And Jesse really only wants two things out of life - he wants the attention of his hippie music teacher who has the face of an angel, and he wants to be the fastest boy in the fifth grade.

Every morning he wakes up before the rest of his family begins their day, and he runs around the pasture on their farm, pushing himself as hard as he can. He runs to forget the loneliness he feels within his own family, he runs to make his father, a long haul trucker often on the road, proud. He runs to impress the music teacher, Miss Edmonds. He runs to hide his secret love of art and music, a secret that would earn him the reputation of being a sissy. He wants to be the fastest, so what he is inside can be hidden by what is seen on the outside: The Fastest Boy in the Fifth Grade. His fame will make him invisible, safe. And then one morning right before the school year begins, during his last early practice run in the pasture, he meets Leslie.

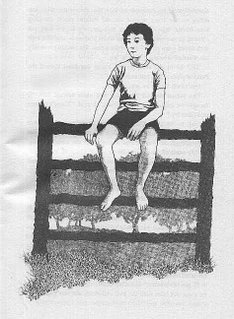

If you're so afraid of the cow," the voice said, "why don't you just climb the fence?" He paused in midair like a stop-action TV shot and turned, almost losing his balance, to face the questioner, who was sitting on the fence nearest the old Perkins place, dangling bare brown legs. The person had jaggedy brown haircut close to its face and wore one of those undershirtlike tops with faded jeans cut off above the knees. He honestly couldn't tell whether it was a girl or a boy.

He paused in midair like a stop-action TV shot and turned, almost losing his balance, to face the questioner, who was sitting on the fence nearest the old Perkins place, dangling bare brown legs. The person had jaggedy brown haircut close to its face and wore one of those undershirtlike tops with faded jeans cut off above the knees. He honestly couldn't tell whether it was a girl or a boy.

"Hi," he or she said, jerking his or her head toward the Perkins place. "We just moved in."

Jess stood where he was, staring.

The person slid off the fence and came toward him. "I thought we might be friends," it said. "There's no one else close by."

Initially, Jess rejects Leslie's overtures of friendship. She doesn't look right, she doesn't dress right, she seems peculiarly unconcerned with how she comes across to the other kids, and worst of all, she's better at being a boy than all the other boys. On the first day of the races, Leslie insists on joining in. To the boys' dismay, Jess included, Leslie wins all the heats in a blowout. She makes it look like she's not even trying.

She ran as though it was her nature. It reminded him of the flight of wild ducks in the autumn. So smooth. The word "beautiful" came to his mind, but he shook it away...

As she turns and stands, smiling, at the finish line, the boys' resentment nearly takes her breath away. Stupid weird Leslie. She ruined everything. She just doesn't know how to act right.

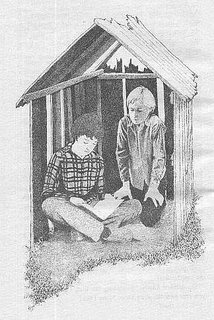

Things get worse for Leslie. She's too smart. Her eyes shine too brightly. And most shockingly, her family doesn't own a TV. As the mockery of Leslie increases, Jess begins to feel protective of her. Soon they become friends, and as their friendship grows, Jess realizes that the angel isn't Miss Edmonds; it's Leslie. Jess succumbs totally to Leslie. She becomes the most powerful presence he's ever known. She lifts him up from the despair of his poverty-stricken rural world and offers him hope, salvation, and the possibility of freedom. She encourages him to aspire for more than just survival. They become soul mates. Deep in the woods they hide, swinging over the craggy ravine on a rope, Tarzan-like, to reach the pine forest, where the trees grew thick at the top and the sun shown through like a veil. Here Leslie and Jess create a magic world, Terabithia, for just the two of them. Here, Jess can play and draw and laugh, away from the judgment of his family and his peers.

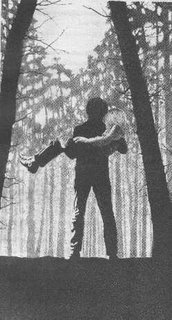

Jess succumbs totally to Leslie. She becomes the most powerful presence he's ever known. She lifts him up from the despair of his poverty-stricken rural world and offers him hope, salvation, and the possibility of freedom. She encourages him to aspire for more than just survival. They become soul mates. Deep in the woods they hide, swinging over the craggy ravine on a rope, Tarzan-like, to reach the pine forest, where the trees grew thick at the top and the sun shown through like a veil. Here Leslie and Jess create a magic world, Terabithia, for just the two of them. Here, Jess can play and draw and laugh, away from the judgment of his family and his peers.

As soon as it becomes clear that Leslie is the embodiment of religion, Paterson does the unthinkable: She proves there is no God.

I remember finishing this book as a child, not much older than Alex is now. Tears streaming down my face, crying, "It isn't fair! How could this happen? How could this happen to me?"

There wasn't a detached musing about the events in the book. The pain I felt was raw and real, and hit me harder than any book ever had. Jess and Leslie weren't cartoon characters. They weren't zany and funny and they didn't get into crazy, mixed-up scrapes. They looked and acted like real kids, with real concerns and dreams. They could have been anybody I knew, and when I realized that, I was horrified. I took it very personally. It wasn't even until I was an adult that I accepted the ending of the book. In my resentment toward Paterson, I never noticed how neatly she sews up the ending, that his newly-found passion and strength win the respect of his aloof father more than winning a fifth grade race ever could, and most importantly, by opening his mind and heart Jesse discovers that salvation lies within himself.

It wasn't even until I was an adult that I accepted the ending of the book. In my resentment toward Paterson, I never noticed how neatly she sews up the ending, that his newly-found passion and strength win the respect of his aloof father more than winning a fifth grade race ever could, and most importantly, by opening his mind and heart Jesse discovers that salvation lies within himself.

I can pick up on those more subtle lessons now, and all the social, political, and class issues Patterson peppers thoughout the book that lie in thick layers, like the needles carpeting the floor of Leslie's Pine Forest.

I just can't drop Bridge to Terabithia on my babies like an atom bomb. I discovered it myself at the library when I was eight or nine, and I think the independent discovery of such a profound novel was what caused it to be the most influential book of my childhood.

I'm going to slip it back quietly onto the shelf now, and leave it alone. Someday, when the boys are ready, it will be waiting for them.

________________

Bridge to Terabithia

by Katherine Paterson

illustrated by Donna Diamond

Harper Classics

Reissue edition 1987

ISBN: 0-064-40184-7

Thanks to Hennessey Catholic College for uploading Donna Diamond's original artwork.

Saturday, November 11, 2006

<< Home