Siberia

O Comrades! I have fallen in love with another bleak graphic novel about living in a Totalitarian regime. Let the relentless urging for everyone to read it begin again!

Although not as weird as life depicted by my boyfriend* Guy DeLisle’s best comic evar, Pyongyang, Nikolai Maslov’s Siberia is definitely more grim. While DeLisle knew his time in Pyongyang would come to an end, only a few months spent in the world's last Communist country, he was able to maintain a humorous, wry detachment from life in the shadow of Kim Jong Il’s bouffant. Maslov’s perspective, however, is that of someone born and raised in pre-Perestroika Siberia, with very little hope of escaping the hammer and sickle.

There is a common Russian expression, “When you’re part of a flock, it doesn’t matter who’s first and who’s last.” With such a motto of resignation adopted by his countrymen, what is most amazing about the book is Maslov’s seemingly unflagging determination that no matter what, he would never stop trying to be first. It reminded me of the old Far Side cartoon with millions of identical penguins milling around, and in the middle of the crowd, one rises up, wings upraised, singing, “I’ve just got to be me!”

And after almost half a century of struggling to break out of the endless cycle of poverty and depression to become an artist and create something genuinely beautiful, he did it.

Siberia is a graphic novel written by a nearly lifelong resident of Siberia, a middle-aged night watchman who had never even seen a graphic novel when he picked up his pencil and began to draw.

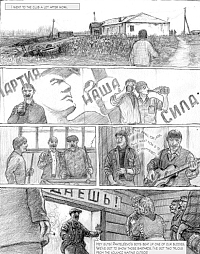

“My story is neither the most violent, nor the most tragic,” he writes, and as his life unfolds, the image of millions of people living an entire lifetime with no real hope is almost overwhelming. His story begins in 1971, in Western Siberia, and from the very first pencil sketch, showing a desolate strip of road surrounded by log cabins in the mud, an image right out of 19th century Chekov, the strong desire to escape from such a place is evident. With the blackest of humor, he shows himself in school, listening to his teacher tell the students, “…Thanks to the guidance of the Communist Party, we live in the world’s richest country.” Then he contrasts the reality of Siberian life, sketching his young self watching miserably, as unhappy men succumb to their only passion, vodka, while he wonders when he would take his place among the same unhappy bar patrons.

His story begins in 1971, in Western Siberia, and from the very first pencil sketch, showing a desolate strip of road surrounded by log cabins in the mud, an image right out of 19th century Chekov, the strong desire to escape from such a place is evident. With the blackest of humor, he shows himself in school, listening to his teacher tell the students, “…Thanks to the guidance of the Communist Party, we live in the world’s richest country.” Then he contrasts the reality of Siberian life, sketching his young self watching miserably, as unhappy men succumb to their only passion, vodka, while he wonders when he would take his place among the same unhappy bar patrons.

Siberia is drowning in vodka. It is the only thing the rural Soviets felt they had to live for. In a particularly striking moment, Maslov shows two panels, the first of a store, its shelves nearly empty, worn boots lined up next to four sauce pans. The next panel is that of a woman, mouth open with joy, holding a bottle of vodka in each hand. Behind her are hundreds of gleaming vodka bottles wedged tightly together on brightly lit shelves. The message is clear: there is nothing else here.

From his compulsory service in Mongolia, Maslov only dreams about a few moments of escape from his life of servitude, going AWOL from time to time to explore the mountainous countryside and willing taking the 40 days of solitary confinement as punishment just for the chance to indulge his yearning to be free. These moments of escape are when he allows himself to show the wild beauty of his homeland, and his love and loyalty to his country shine through. In a gorgeous sketch of the sun streaming through the trees, he manages to make the pencil gray seem blindingly bright. During his service, instead of trees, he draws sausages on propaganda posters. “The only place we ever saw them,” he remarks dryly.

After his discharge, he heads to Moscow where he can at last attend art school, only to learn that his lack of political connections will not get him very far. He also learns that in Moscow, getting far as an artist means a lifetime of showing “the great advantages of the Soviet way of life.” Great, more sausages.

Despite the unrelenting hardship of his life, Maslov approached a Soviet publisher in 1996 and showed him 3 pencil sketches. Shyly, he pitched his book. After reviewing the sketches, the publicist took an almost unheard of chance on Maslov and paid him an advance, allowing him to quit his night watchman job for three years and tell his life story. When it became published internationally, first in France, now in the United States, Maslov flatly refused to believe it was true.

Perhaps because of his lifelong struggle to stand out among the millions and have his story finally told, the lesson Maslov seems to want to get through is this:

“…what you have to look for in life is truth and kindness. Otherwise, what’s life for?”

__________________________

*I have many, many boyfriends, none of whom have ever met me.

___________________________

Siberia

By Nikolai Maslov

Translated by Blake Ferris

2006 by Soft Skull Press

ISBN: 1-933368-03-9

Sunday, November 12, 2006

<< Home